The Kingdom of Benin

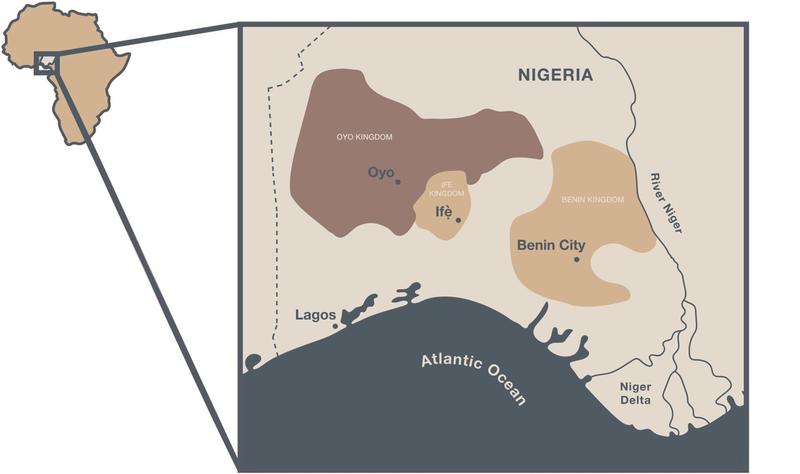

The Benin kingdom, also known as Edo, was founded around 900 CE. It was one of the most important kingdoms in West Africa, located in present-day Edo State, Nigeria. Its densely populated capital, Benin City, was located at the heart of an extensive trade network for cloth, pepper, ivory, and salt which moved across West and Central Africa and the Atlantic Ocean. Edo people moved into the Niger River basin to settle and form the kingdom, ruled by the Ọba (king). The kingdom was established in a tropical rainforest with trees giving kola nut, palm oil, and raffia palm fibre. It was surrounded by land for growing plants such as cotton and yam. By the 1500s, when some of the earliest objects in this case were made, it was a planned city with streetlamps, drainage systems, earthen walls and iya (moats). Today Benin City is a thriving cosmopolitan city, the fourth largest in Nigeria. It remains a cultural centre for guilds of artisans and is the spiritual home of the Edo people. Benin City is also home to the palace of the Ọba, who serves as a ceremonial leader.

The Pitt Rivers Museum is deeply grateful to Uwagbale Edward-Ekpu and Prof Kokunre Agbontaen-Eghafona for their time and expertise in the co-curation of the display.

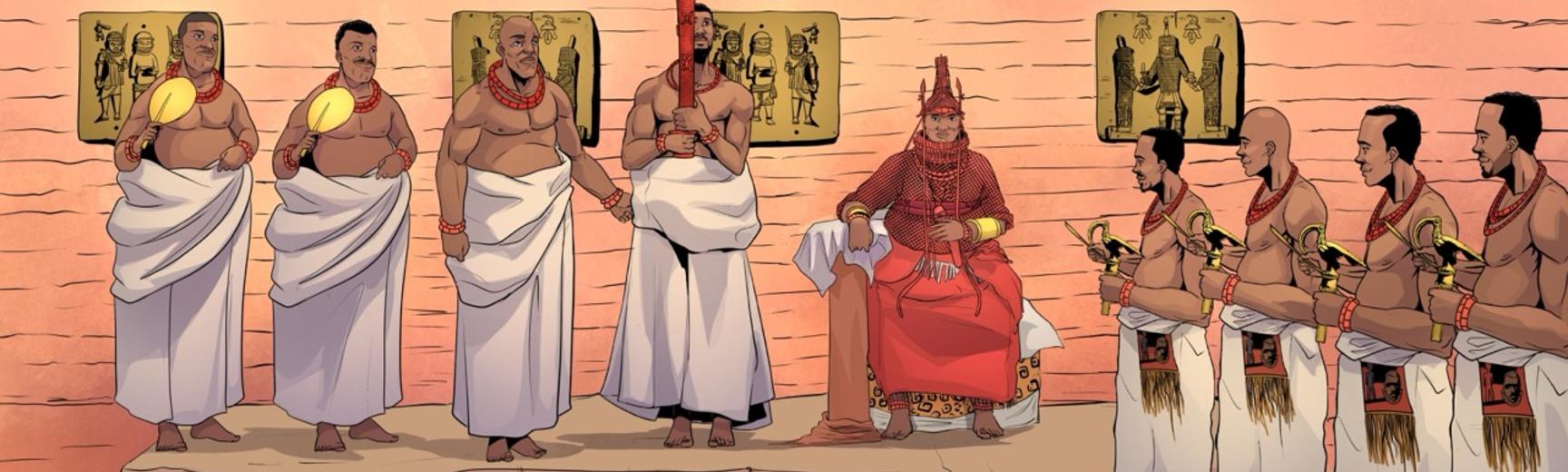

Illustrations based on historical sources by Uwagbale Edward-Ekpu and Onaolapo Rilwan Ayomide.

Ọba

The Ọba, as ruler of the kingdom, wore the finest woven cloths and Akpa (a net shirt with coral beads) to show his power and authority. Collar necklaces or armbands made with Ivie and Ẹkan (coral and agate beads) showed the status of the wearer. Coral and agate were rare materials, brought through trade networks from the Mediterranean Sea and northern Africa. The chiefs held objects such as the Ahianmwẹ-Ọrọ (bird of prophecy staff) and Ẹzuzu (fans) in the presence of the Ọba to honour him. Brass and bronze plaques depicting notable historical scenes were prominently displayed on the walls of the palace. The use of many of these materials in ceremonies continues to this day.

Altar and Sound

Ancestral altars dedicated to past Ọbas and Iy’Ọbas (Queen Mothers) had prominent locations in the palace. They are a core element of Edo ancestral worship and some of the most intricate sculptures are displayed there, showcasing the skills of the city’s artisans. Lifelike statue heads made of bronze or brass commemorated individual Ọbas and Iy’Ọbas. Other cast works showed scenes of life in the kingdom, such as the Urhotọ displayed in this case of the royal procession of a queen and her attendants. Brass bells summoned the spirits of the ancestors during prayers and ceremonies. Ikpakohẹn (musicians) played Oko (side-blown elephant ivory trumpets) to herald the presence of the Ọba, and to share news such as births and deaths.

Ceremony and Food

Evbere (kola nuts) are revered across West Africa as a sacred food, part of ritual gatherings and important occasions. In Edo culture, kola nuts are a symbol of friendship and respect. Intricately carved vessels were created to share food during ceremonies, enhancing the value of the food as a gift or offering. The coconut cup, the ivory bowl, and the Ẹkpẹtin (wooden container) shaped like an antelope’s head in this case are examples of these vessels. The antelope container was likely used in a religious context, as the antelope is linked to sacrificial offerings.

Adornment

As the Benin kingdom grew, hierarchy was publicly shown through adornment. Chiefs had Ebẹn (ceremonial swords) and wore brass, bronze, or ivory pendants depicting animal and human figures. Uhunmwu-Ẹkuẹ (pendant masks) provided protection during battles and ceremonies, such as the leopard pendants with small bells worn by warriors or ivory pendants worn by top chiefs. The Ọba and chiefs wore Ikoro (wrist bands) made of brass and ivory and intricately decorated with Edo and European faces, crocodiles, leopards, and mudfish.

Iy’Ọba

Iy’Ọba was a title first given to Queen Idia, the mother of Ọba Ẹsigie, in the late 1400s. The Iy’Ọba had an important role as a senior advisor to the Ọba and the kingdom. The Iy’Ọba had her own palace and participated in war, commanding her own military regiment. The Iy’Ọba is the most revered female in Edo royal ancestral worship and after her death, the Ọba commissions objects for her personal altar in the palace. The last Iy’Ọba was Princess Eghiunwe Akenzua, who was given the title in 2016.

Guilds

Benin City was divided into Idumu (quarters) named after the guild that worked and lived there. Guilds were created for all types of work: ivory and wood carving, metal working, weaving, butchery, dancing, medicine and divining. Certain families became associated with guilds for many generations. The Igbesanmwan (guild of ivory carvers) carved the intricate tusks which recorded historical events in the kingdom. Igun Eronmwon (guild of metal casters) smelted metals and created figures and plaques using the lost wax method, where molten metal is poured into a precisely carved wax and clay mould.

In February 1897 British troops, including African auxiliary soldiers and local carriers, attacked Benin City in Nigeria with an overwhelming force. They did so both in retaliation for a deadly attack on a group of unarmed British officials and traders the previous month but also to extend British economic control of the region.

Photograph: Reginald Kerr Granville, 1897 [PRM2019.32.2.53]

In little more than a week Benin City was captured and burned to the ground. It isn’t known how many villages were destroyed along the way, or how many Nigerian people were killed or injured, but it is likely to have been hundreds. This was an intentional act, to “increase the punishment inflicted on the nation.”

Photograph: Reginald Kerr Granville, 1897 [PRM2019.32.2.68]

By the time troops arrived, most of the inhabitants of Benin City had fled. The invading troops found many abandoned homes, as well as evidence of human sacrifice. Any remaining chiefs were captured, and a search began for the Ọba, who had escaped.

Photograph: Reginald Kerr Granville, 1897 [PRM1998.208.15.9]

In the Ọba’s compound, the British troops found large quantities of plaques and statues made from bronze and brass, which they seized. Some of these amazing artworks were hundreds of years old, the work of generations of expert metal workers.

Photograph: Reginald Kerr Granville, 1897 [PRM1998.208.15.11]

Also seized were many intricately carved elephant tusks, such as the ones in this display. These prestigious objects told stories about the history of the Benin kingdom and its religion. They were now considered valuable assets by the British Foreign Office who were keen to sell them and defray some of the costs of the campaign.

Photograph: Reginald Kerr Granville, 1897 [PRM1998.335.5]

The seized artworks of the royal court were gathered and guarded, apparently to deter looting by soldiers. However, many of the objects were then allocated to officers and other servicemen as booty. Most of the objects in this display were acquired in this way by officers who either sold them to museums or later donated or loaned them.

Photograph: Reginald Kerr Granville, 1897 [PRM2019.32.2.46]

The Pitt Rivers Museum's collection from the Kingdom of Benin consists of around 150 objects and XX photographs as well as unique manuscript items such as diaries and reports by colonial officers.

The collection has been digitised and made available online via the Digital Benin project portal.

The Pitt Rivers Museum recognises the looted status of the material in this display and is committed to ongoing dialogues with the Nigerian Government as well as the Royal Court of Benin, relevant communities, and activists to discuss the future of these objects and their interpretation.

As part of this, the Museum has been involved in the Benin Dialogue Group, an international meeting established in 2007 with Nigerian and European partners that has led the way in looking for an equitable future for these objects.

On 20 June 2022 the Council of the University of Oxford considered and in principle supported a claim by the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments for the return of 97 objects that were taken from Benin City by British armed forces in 1897. The University has recommended the legal transfer of ownership of the objects to Nigeria.

As of Summer 2025, this process is still pending.

Image © MARKK 2023

Interested in our provenance research on the collection?

Graham Lacdao / St Paul's

Still Standing is a specially-commissioned mixed-media artwork by Nigerian-born artist Victor Ehikhamenor, acquired by the Pitt Rivers Museum in 2022 with generous support from Art Fund.

The work forms part of 50 Monuments in 50 Voices, a partnership between St Paul’s Cathedral and the Department of History of Art at the University of York, which worked with contemporary artists, poets, musicians, theologians, performers and academics to showcase their individual responses to 50 historic monuments across the Cathedral.

Based in Lagos, Nigeria, and Maryland, USA, Ehikhamenor is renowned for his broad practice comprising painting, sculpture, photography, and unique works on paper. His richly-patterned works use symbolism from both traditional Edo religion and Catholicism, reflecting on the confluence of African and Western cultures. Still Standing combines rosary beads and Benin bronze hip ornament masks to depict an

Ọba of Benin.

Still Standing was commissioned and curated by the PRM's Curator of World Archaeology Dan Hicks and Simon Carter, Head of Collections at St Paul’s Cathedral. The installation responded to a 1913 brass memorial panel in St Paul's dedicated to Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson (1843-1910) who had a long career in the Royal Navy, which culminated in his commanding the Benin Expedition of 1897.

Artist Victor Ehikhamenor has said about the work:

History never sleeps nor slumbers. For me to be responding to the memorial brass of Admiral Sir Harry Holdsworth Rawson who led British troops in the sacking of the Benin Kingdom 125 years ago is a testament to this. The installation Still Standing was inspired by the resolute Oba Ovonramwen who was the reigning king of Benin Kingdom at the time of the expedition, but the artwork also memorializes the citizens and unknown gallant Benin soldiers who lost their lives in 1897 as well as the vibrant continuity of the kingdom till this day. I hope that we, the descendants of innumerable uncomfortable thorny pasts, will begin to have meaningful and balanced conversations through projects such as 50 Monuments in 50 Voices.

Curator Dan Hicks said, “this specially-commissioned work opens up a unique space for remembrance and reflection. Still Standing reminds us of the ongoing nature of the rich artistic traditions of Benin, of the enduring legacies and losses of colonial war, and of the ability of art to help us reconcile the past and the present.”

Aken Akota / Aken Owie Evening Tusk / Morning Tusk

Isaac Erhabor Emokpae (born 1977)

At the east end of the museum, either side of the Haida Star House Pole, are two 8-metre-high paintings by Benin artist Isaac Erhabor Emokpae. They were made in response to a carved ivory altar tusk looted from Benin City in 1897. The tusk, which can be seen in the Kingdom of Benin display, was burnt in the conflagration that engulfed the Oba’s Palace during the British attack on Benin City.

Emokpae explains:

When I saw that tusk, I was transported right back to the day when the fire was burning. It was singed and burnt, a forensic remnant of that violent campaign. But, like Benin culture, it survived, and the story still continues.

Duality is important in Benin philosophy. One scroll evokes the dark night of colonial violence. The other scroll is about hope and rebirth. Whatever was buried under colonialism didn’t stay buried: it kept growing. Now everyone knows about Benin culture.

Night and day: Emokpae’s diptych evokes the darkness of colonial violence, but also the survival of the Benin people and hope of a brighter future.

In the style of the Benin carvers’ guild, Emokpae depicts a mixture of traditional and modern figures, reminding us life goes on. The descendants of the ancestors shown on the original tusk are now lawyers, doctors and media professionals.

Emokpae initially created the diptych live during a public event at the Pitt Rivers Museum in May 2024 entitled The Gathering Place which brought African and British artists of African descent together to perform in response to the collections and how they might be reimagined.

The event was also the showcase for the Taruwa project, which brought five Nigerian artists/performers to engage with collections in the museum, which spoke to their identity and heritage.