Footprints in the Sands of Time

What traces of our lives do we leave behind us? Can photographs change how we are remembered?

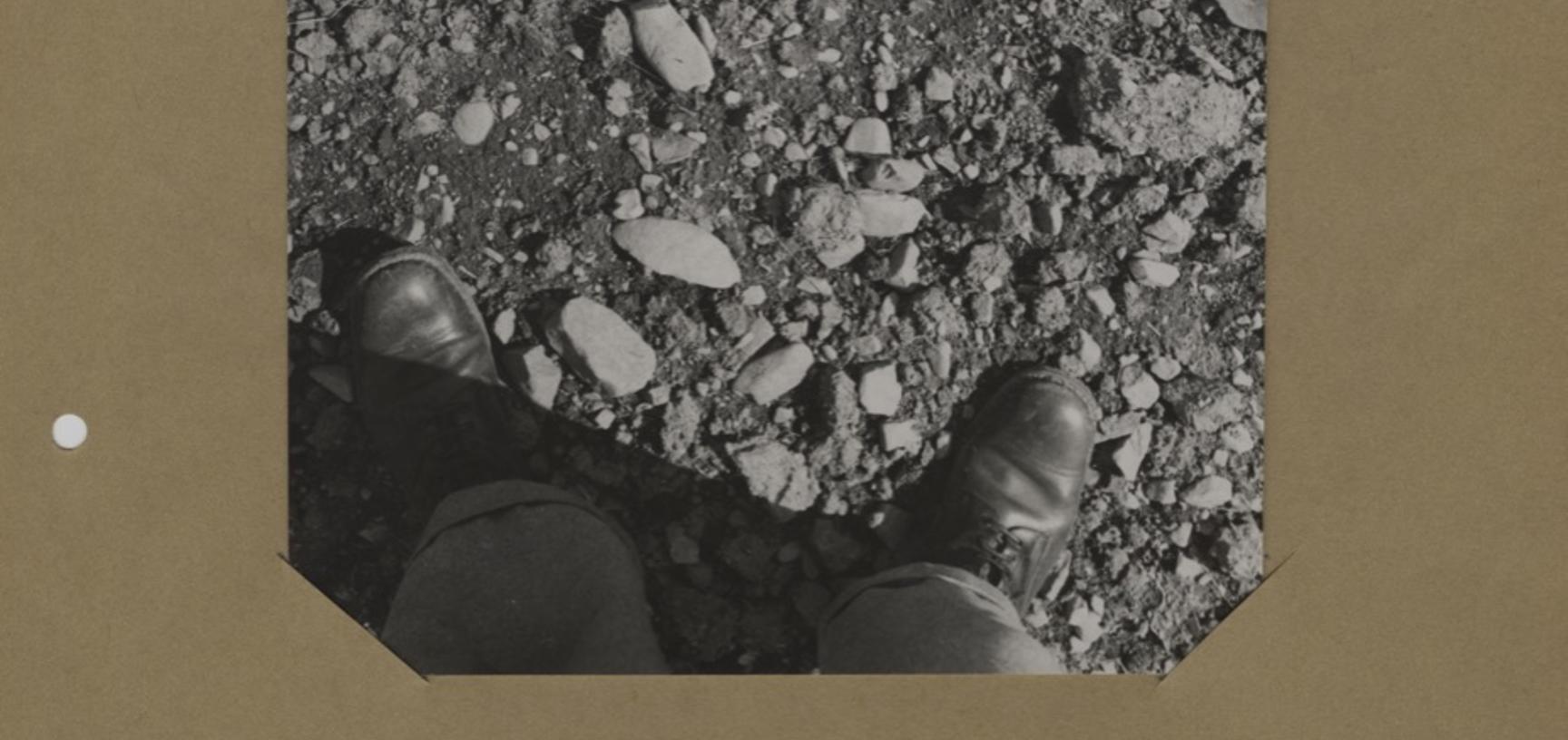

On 19 January 1952 archaeologist Osbert Guy Stanhope Crawford (1886–1957) scrambled up the side of a sand dune, leaving behind a trail of footprints. But before he felt able to walk on the dune, he photographed the patterns the wind had made in the sand. That day he mused in his diary: ‘The sand dunes are very beautiful with their graceful ribbed slopes and sharp converse tops. I took some views… before we began to walk over them… Our footsteps in these sands of time will be obliterated by a few strong winds’. Crawford was quoting from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s ‘A Psalm of Life’ (1838). This poem directs readers to draw inspiration from the lives of ‘great men’ and to leave their own tangible mark on the world for future generations.

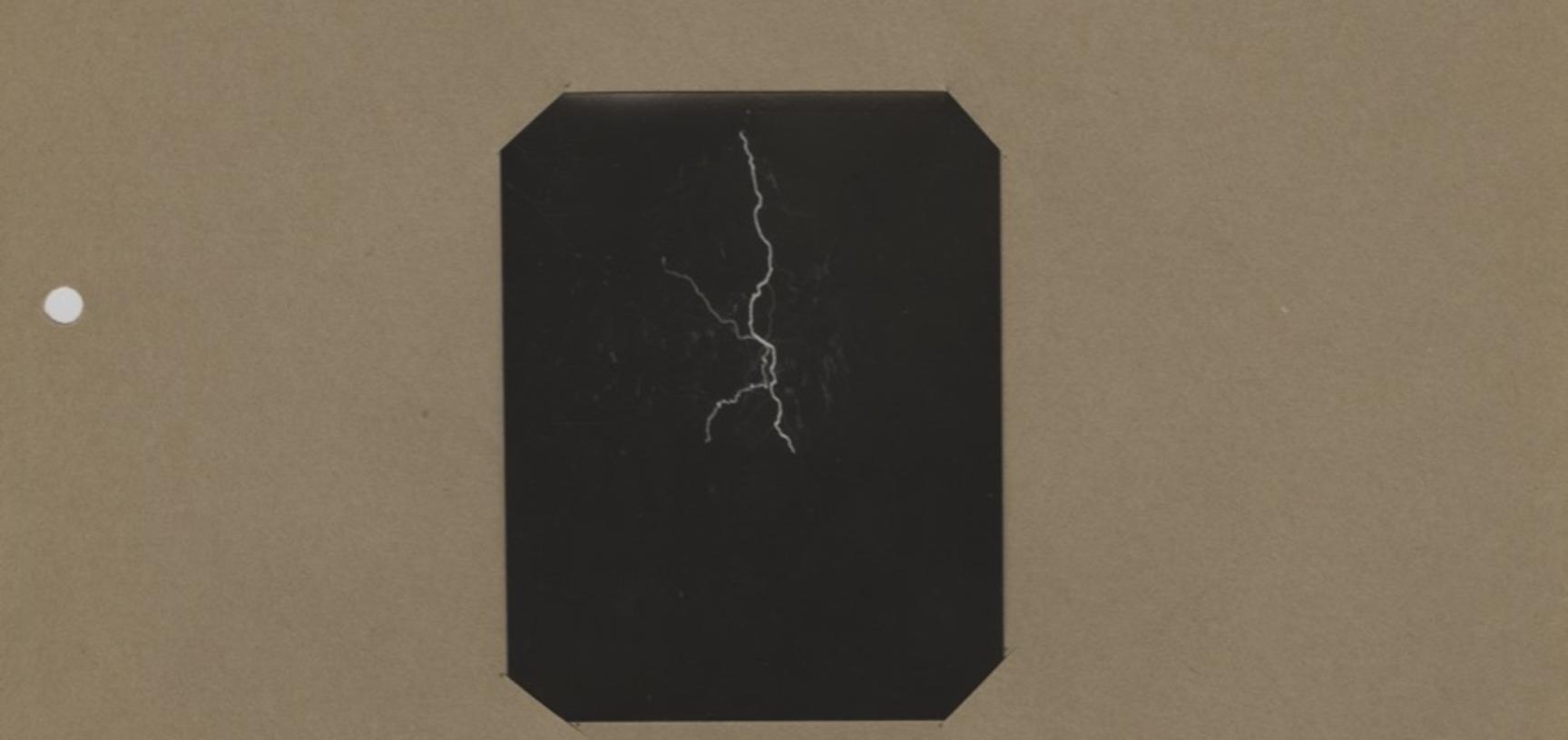

Crawford is famous for being one of the first archaeologists to use aerial photographs to identify archaeological sites and for his book Wessex from the Air (1928). Crawford was an enthusiastic photographer, taking over 10,000 photographs in his lifetime, which are preserved within the Institute of Archaeology, University of Oxford. Ironically this archive contains few aerial photographs. Instead, the images – taken with Crawford’s feet firmly on the ground – span an incredible range of themes, including archaeological excavations, studies of weather patterns and even snapshots of pets. These photographs show a different, more personal side to Crawford, in comparison to his professional public persona.

Crawford actively thought about his legacy. He published an autobiography Said and Done (1955) and edited old papers in his archive, even making arrangements for his personal and political papers to be burned after his death. On one document Crawford wrote ‘This is a terrible collection of rubbish… I have refrained from destroying it with great difficulty’. Crawford began to label himself in photographs, ensuring that he would be clearly identified in the future.

Published records of Crawford’s life and work are heavily edited, making it difficult to understand Crawford and how he practised archaeology. However, the photographs from his archive cast new light on his personal life and work, even revealing hidden voices in the history of archaeology. This exhibition explores some of these stories…

Life in the Archive

When does a collection of photographs become an archive?

People sometimes imagine archives as places where nothing changes. But collections of material do develop, grow and change, they just do so over much longer periods of time. This means that we have to think about how Crawford’s archive developed over the course of his whole life.

Crawford was an active photographer from a young age; early images show Crawford with his aunts (who raised him), his childhood pets and his old schoolmaster at Marlborough College, C. G. Bell. The image of Bell is one of the earliest taken by Crawford, probably around 1903. In his autobiography Crawford said his school days were ‘years of misery’; however, it was at Marlborough he first showed an interest in archaeology.

Crawford’s skill with a camera led to him being tasked with taking panoramic shots of the front lines during the First World War. Crawford said the war cured him of being ‘over-confident and priggish’ but it also had a far more traumatising psychological effect. By the end of the war Crawford had completely given up photography.

Following the war Crawford roamed the countryside taking on a number of archaeological projects. On one occasion he caused a scandal by meeting members of the Cambrian Archaeological Association dressed in shorts. His friend Mortimer Wheeler wrote about this incident ‘my heart warmed to that unmentionable apostate… and his boyish glee in calling the bluff of convention’.

Finally in 1931, encouraged by a friend while on holiday in Austria, Crawford picked up a camera once again. The image of Crawford casually reclining on a bench is one of the first photographs taken with his new Voigtlander camera. The following year Crawford began making a record of the photographs he took. Over time this developed into a register of negatives that can still be used to trace key events in Crawford’s life.

Cats, Clouds and Collecting

Crawford collected and shared photographs with friends and colleagues.

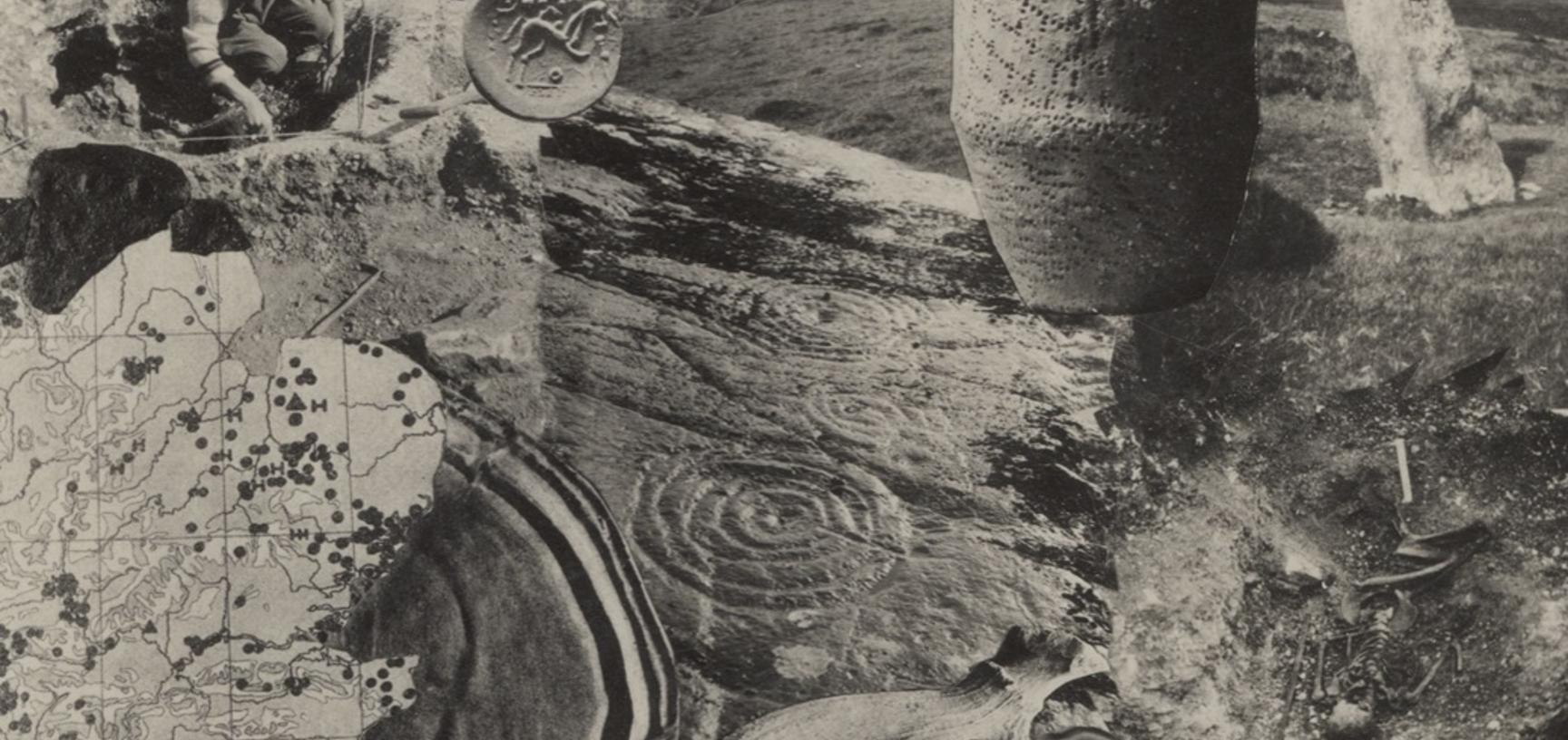

In 1927 Crawford founded the journal Antiquity, which is still published today. Through the journal he developed a circle of contacts, who shared his ideas about archaeology, and used this network to collect photographs taken by colleagues for his archive. When archaeological discoveries were made Crawford, and other archaeologists, exchanged photographs of the finds and discussed how best to interpret them. Crawford sometimes annotated prints with his colleagues’ interpretations. Photographs were important tools for constructing archaeological knowledge, they weren’t just illustrations to be looked at.

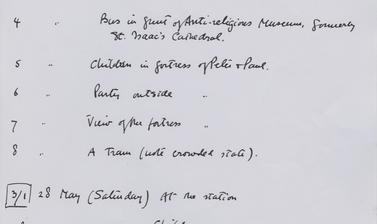

Photographs were not always used for serious research and were sent around archaeological circles as jokes or greetings cards.

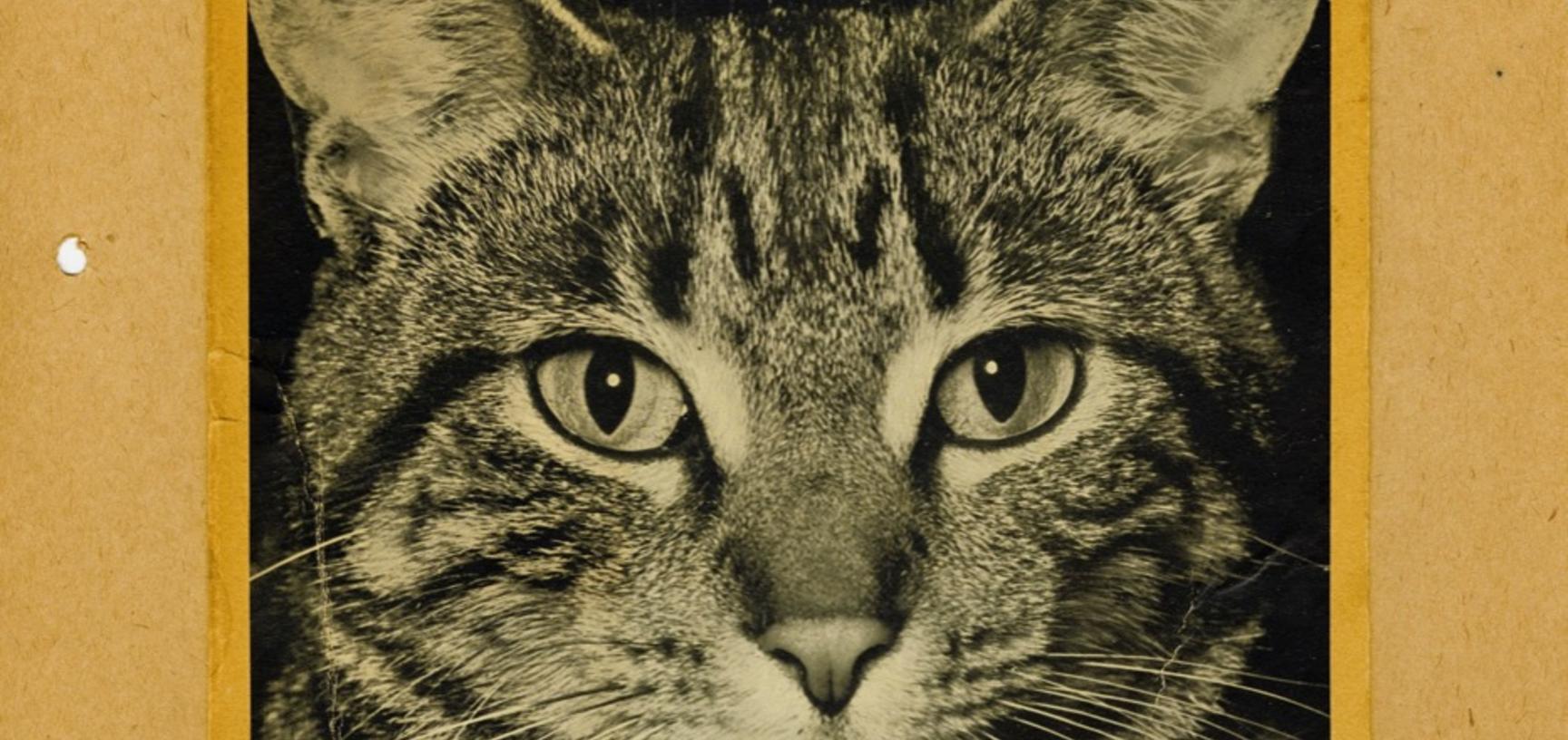

Photography was a social activity for Crawford; he would often arrange to meet friends to photograph all kinds of subjects, including the weather. Crawford’s archive includes many personal items, like a collage made by the archaeologist Stuart Piggott. In this way the archive captures traces of the lives of many people, not just Crawford. The archive even records moments from the lives of animals too. In one letter Crawford apologises to a friend for the presence of paw-print on the paper, as his cat had been sleeping on his writing desk. He had a lifelong love of cats, once appearing on a radio show to demonstrate cats had their own language, though he admitted it was mostly ‘terms of abuse’!

Friendship and Fieldwork

Photography was an essential and highly structured part of excavation.

Between the First and Second World Wars archaeology started to become a recognised job for skilled professionals, rather than a hobby for enthusiastic amateurs. Archaeologists like Tessa and Mortimer Wheeler introduced standardised ways of excavating and recording the results of archaeological work. Archaeological photographs were expected to act as scientific records and books, like M. B. Cookson’s Photography for Archaeologists (1954), described conventions for photographing excavations. Cookson noted that when photographed at work archaeologists ‘must never look directly at the camera and should always stand in a working pose’. Crawford often ignored these rules.

Crawford used photographs to express his personal feelings about other archaeologists.

In 1939 an unprecedented discovery was made in East Anglia of a seventh-century ship burial, which was uncovered by local archaeologist Basil Brown. Once news of this began to spread Crawford offered to join the excavation as the official photographer, hoping to steal a scoop for his journal Antiquity. When the professional archaeologists took over the site Basil Brown was pushed to the sidelines. Brown often appears in the edges of Crawford’s photographs – watching but not allowed to participate. In one photograph the edge of Brown’s wellington boots can be seen peeking out behind one of the finds.

Crawford’s photographs can reveal aspects of excavation rarely written about.

In Crawford’s photographs of excavation disembodied arms and legs crowd into the frame, giving an impression of the cramped spaces archaeologists worked in. Details like these were cropped out when images appeared in archaeological publications. Crawford often incorporated personal anecdotes or humorous annotations on his prints; on one he points out his colleague Charles Phillips’ ‘rear elevation’. Unlike many professional archaeological photographers, who used slow and heavy large format cameras, Crawford used a small and portable Rolleiflex which allowed him to take candid snapshots revealing the close personal friendships between excavators.

Hidden Voices

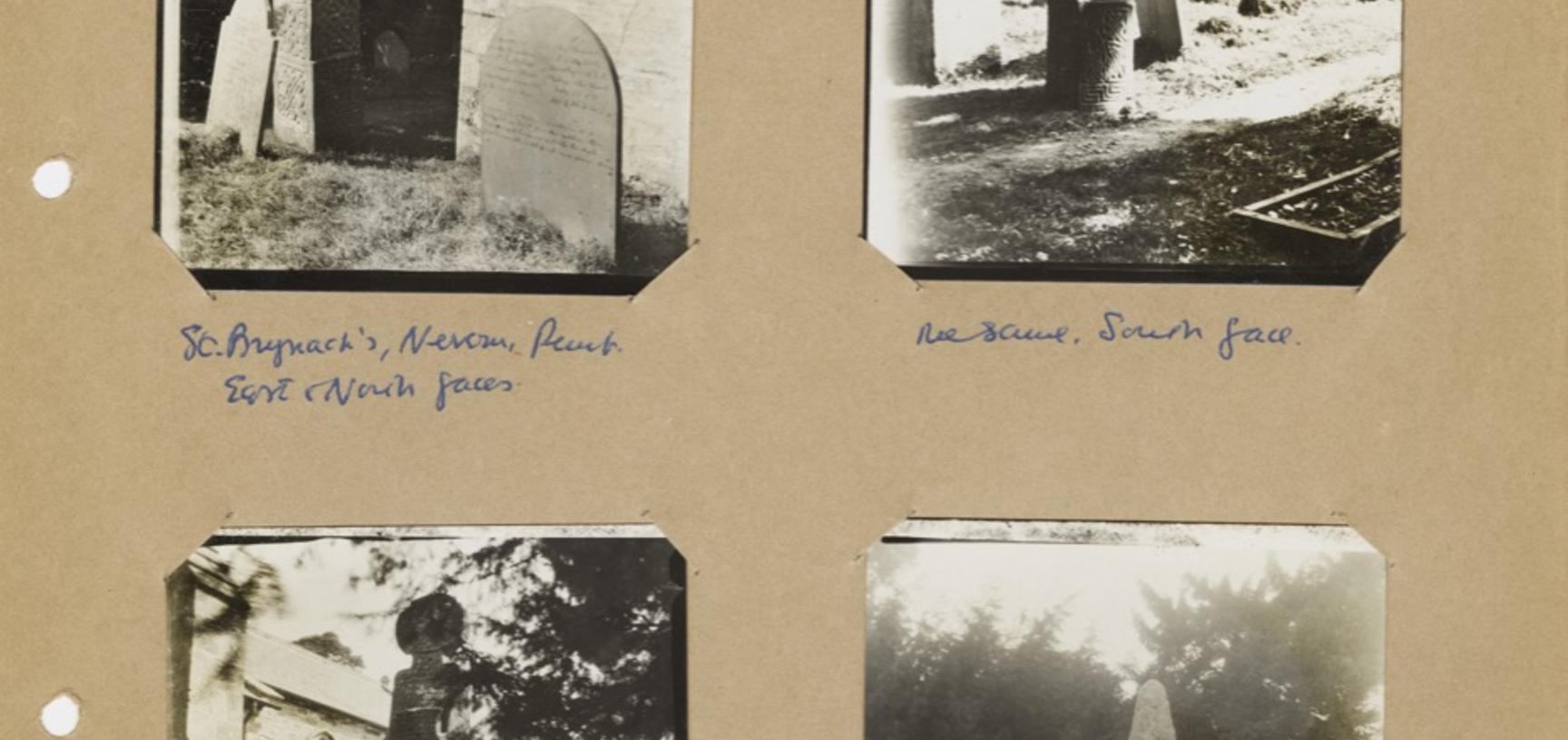

Crawford used photography to bring him closer to his heroes.

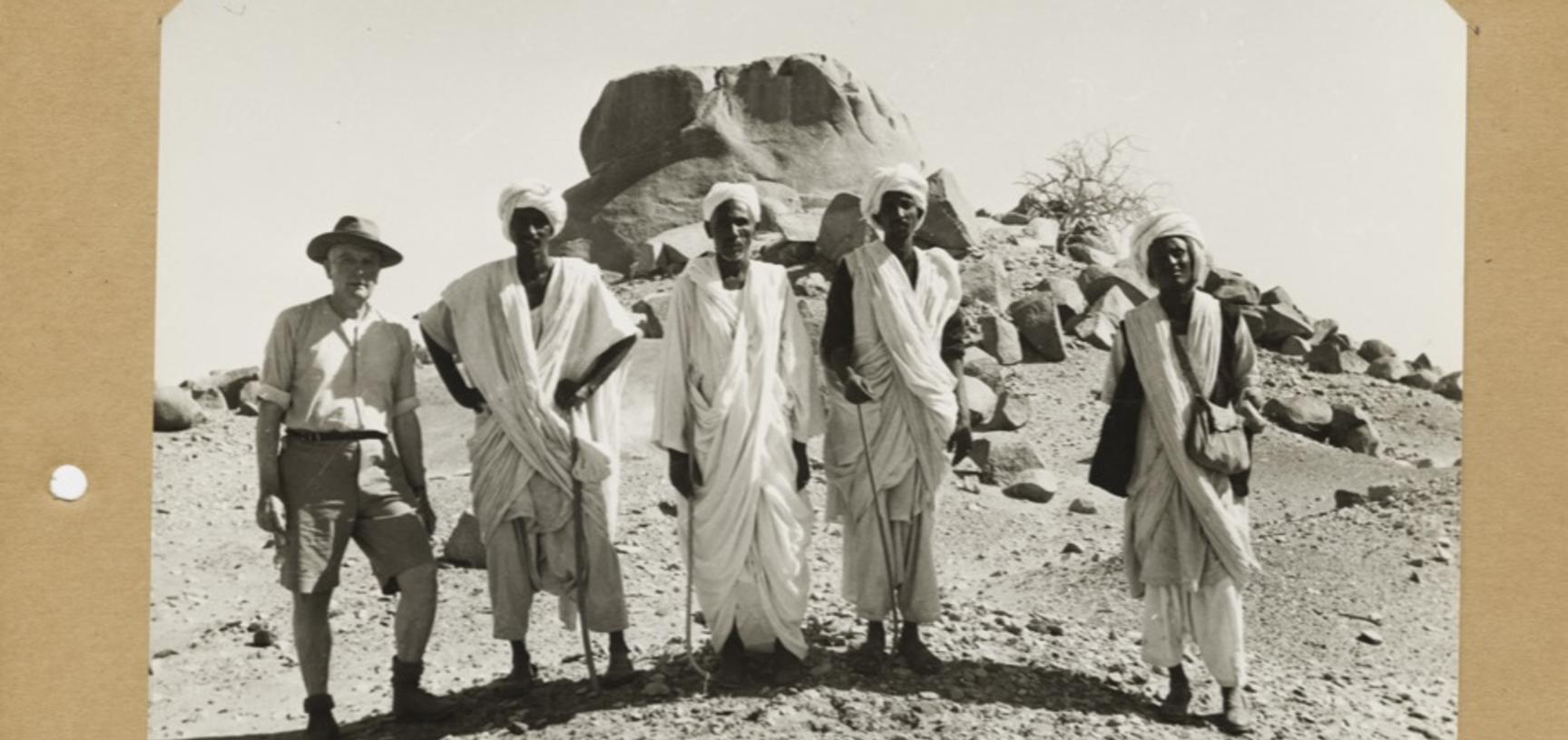

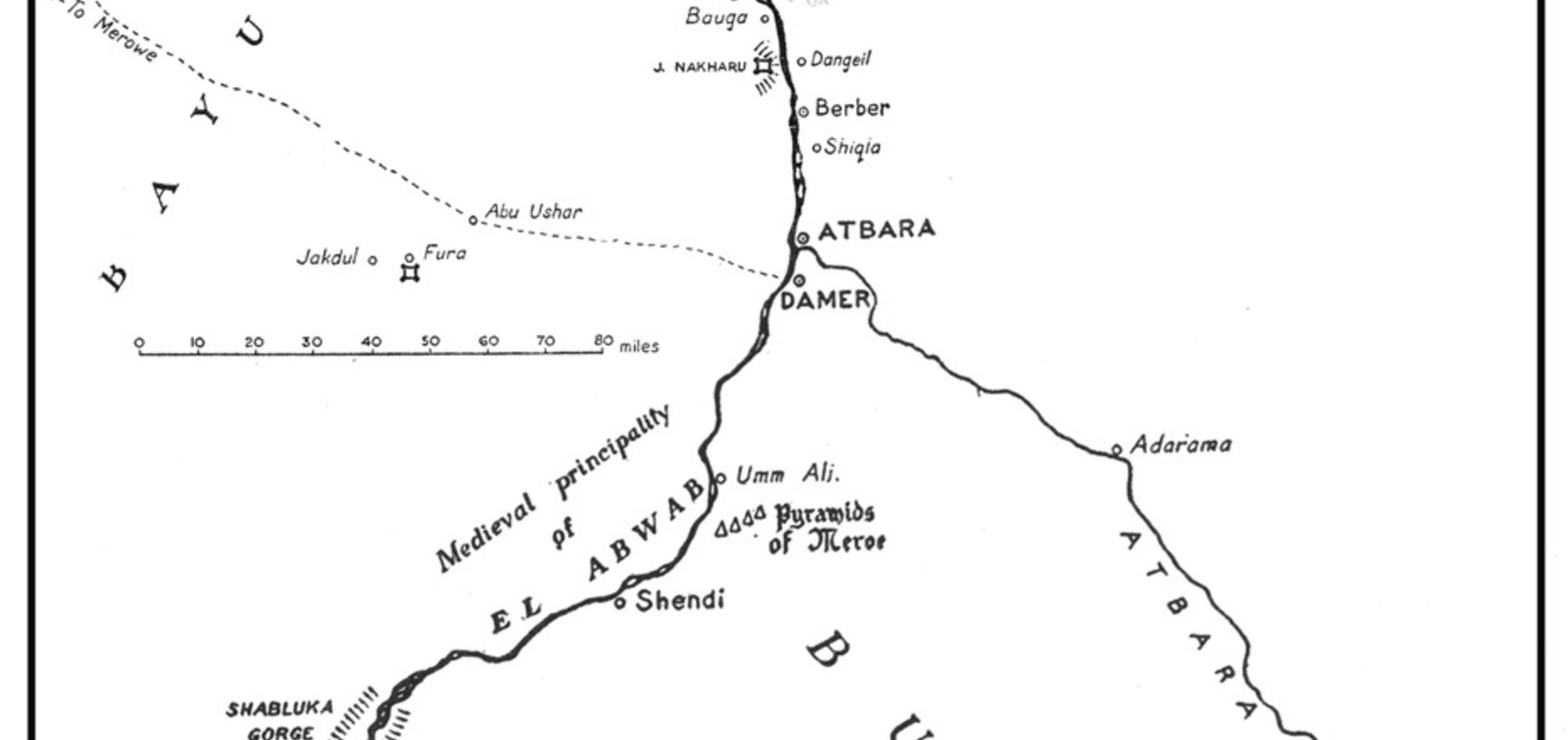

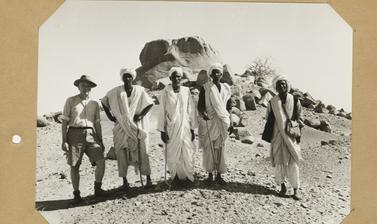

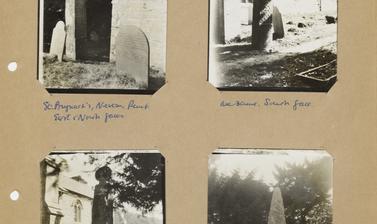

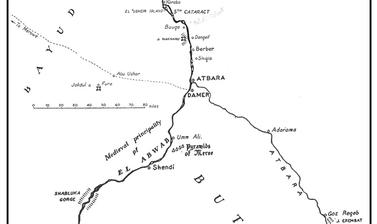

Throughout his life Crawford was deeply susceptible to hero worship and collected ‘relics’ from famous archaeologists and anthropologists, like these photographs of carved stone crosses taken by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie (1853–1942). The pot on display was donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum by Crawford because he believed it had belonged to renowned anthropologist E. B. Tylor (1832–1917). Crawford often tried to emulate his archaeological heroes. In 1952 he received a British Academy grant to undertake an expedition to Sudan, travelling between Abu Hamed and the Atbara River; he described this as the ‘revival of a type of reconnaissance once fairly common’ in the nineteenth century. In Sudan Crawford photographed castles on the Nile from the same viewpoints in the sketches of nineteenth-century archaeologists and Egyptologists – quite literally standing in the footprints of those who had gone before him.

Archives and photographs can obscure histories as easily as they preserve them.

As Crawford travelled in Sudan he was accompanied by a local man called Mohammed Faqir. It was actually Faqir who discovered the sites that Crawford photographed along the Nile. Crawford privately recognised Faqir’s skill, describing him in a diary entry as a ‘first rate field archaeologist’, and labelling him in photographs, a courtesy which he did not extend to Basil Brown.

However, at other times Crawford wrote about Faqir in deeply dehumanising ways, and used him as a human scale in photographs. Crawford’s attitude and the fact that Crawford is still remembered for these discoveries, while Faqir’s role has been overlooked speaks to the systematic racism that was prevalent in archaeology in the twentieth century. Photographs and archives played a role in obscuring the contributions of people like Faqir and Basil Brown while ensuring that we remember figures like Crawford. In the present there is a pressing need to return to archaeological archives to try and uncover these other footprints in the history of archaeology.

Acknowledgements and Credits

- Exhibition curated by Beth Hodgett

- Print design and case installation by Alan Cooke