Human remains in the Pitt Rivers Museum

Since its foundation in 1884 human remains have formed part of the holdings of the Pitt Rivers Museum. These remains originate from different continents and were collected at different points in time. Some of these human tissues, including skin, bone, hair, teeth and nails, have been made or modified into artefacts, such as the well-known shrunken heads (tsantsa) from South America. Many other skeletal remains come from burial contexts. According to our records the founding collection included almost 700 objects which fell into one of these two categories. Due to lack of documentation there are many things we do not know about the human remains in the collections including whether they were taken with permission from family or descendants.

Human remains were collected as a way of supporting academic arguments at the time, that ranked some societies as savage and barbarous and others as civilised. The measurement of bodies and body parts by white people (largely men) was used to uphold racist and sexist beliefs objectifying the bodies of people of colour and women for labour, learning, research, or entertainment. Such ideas persist today and continue to play a part in how some people think about each other.

You’re a race of scientific criminals. I know I’ll never get my father’s bones out of the … Museum... I am glad enough to get away before they grab my brains and stuff them into a jar.

Minik Wallace, Inughuaq from Greenland (in 1909)

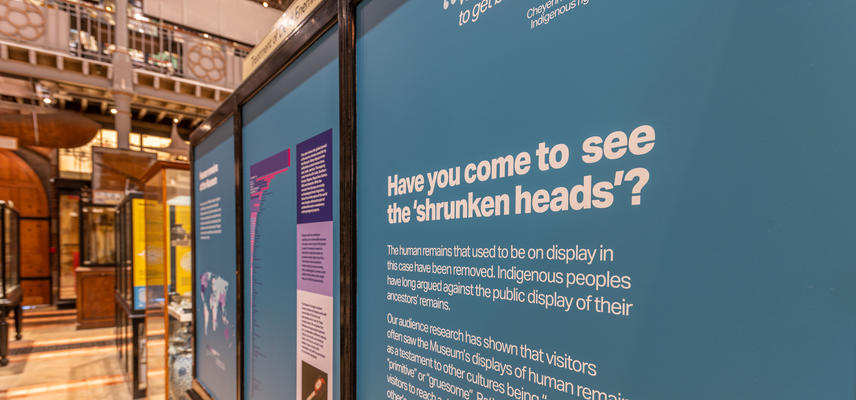

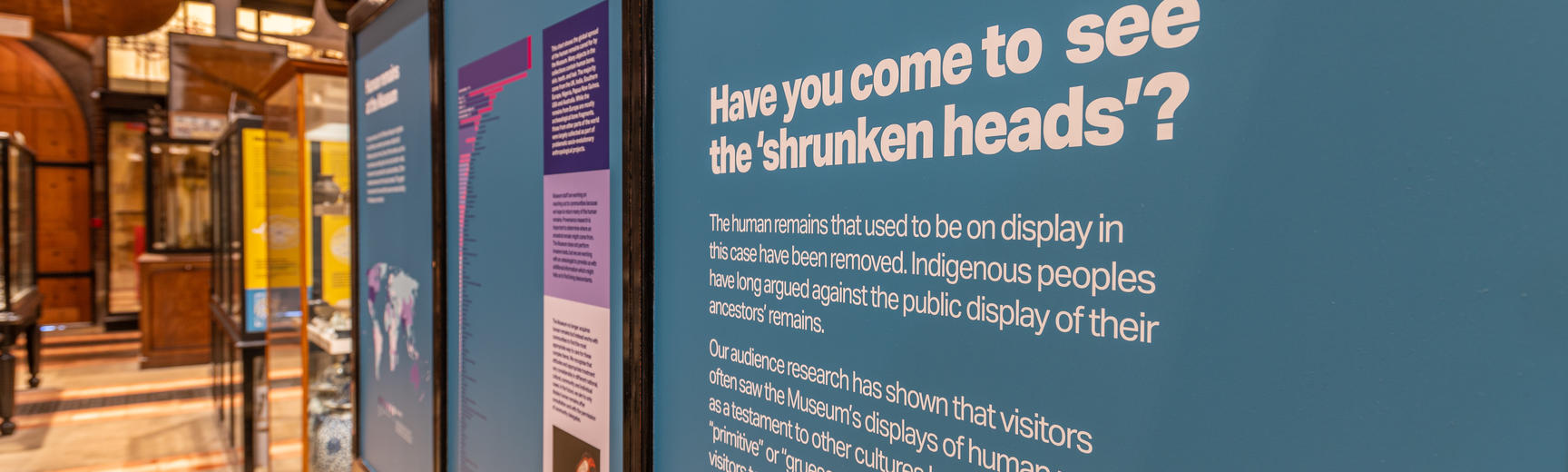

Indigenous peoples have long argued against public display of their ancestors’ remains. In July 2020 the Museum decided to remove all human remains from its galleries. To date 123 items have been removed. However, it is likely that as further research is done and as conversations with community groups progress, other items may be found to include human remains and these too may be removed.

We, too, have the human right to get buried and stay buried.

Suzan Shown Harjo, Cheyenne and Hodulgee Muscogee Indigenous rights activist from USA (in 1996)

Our audience research has shown that visitors often understood the Museum’s displays of human remains as a testament to other cultures being “savage”, “primitive” or “gruesome”. Rather than enabling our visitors to reach a deeper understanding of each other, the displays reinforced racist stereotypes.

By removing human remains from display we seek to show our respect for the communities around the world with whom we work. By consulting with members of these same communities we able to meet international codes of ethics and UK guidelines on the public display of human remains.

Human remains and materials of sacred significance must be displayed in a manner consistent with professional standards and, where known, taking into account the interests and beliefs of members of the community, ethnic or religious groups from whom the objects originated. They must be presented with great tact and respect for the feelings of human dignity held by all peoples.

International Council of Museums Ethical Code, article 4.3

However, as well as the ancestral remains previously on display, there are many more in storage. We do not see these changes to our displays as the end of a process, but as a first step towards redress. Our aim is not to hide this issue but to work with communities to find the most appropriate way forward. Some communities may request the return of their ancestors, and others may wish for us to care for them or treat them differently. We recognise that attitudes and appropriate treatment vary considerably in different national, cultural, community and individual cases. In the future, we aim to only display human remains after consultation and with the permission of community delegates. Given the international origins of the collections, this is a long-term process that will involve collaboration and conversation.

We are focussing on research that helps us determine where remains come from and, where we know, we will be reaching out to communities to make them aware. We are working with an osteologist to provide us with additional information which might help us to find living descendants. This does not involve invasive or destructive testing.

There is a growing awareness among overseas institutions about the importance of repatriating ancestral remains, their genuine commitment to the repatriation of indigenous remains allows our country to resolve a very dark period in our history.

Dr Arapata Hakiwai, Maori and Moriori Karanga Aotearoa programme, Te Papa Museum, New Zealand (in 2016)

The Museum has returned human remains and associated objects and will continue to work with international partners on this important work. Before the Museum can agree to return any remains, we need to be sure that the requesting body speaks for the community of origin and that the wishes of the community are being consulted, accounted for, and followed. For many communities, repatriation remains prohibitively expensive, subject to impassable barriers and is hard to achieve in practice. It may also seem low priority when set against a complex backdrop of other political, social, and cultural challenges. The Museum seeks to address this and meet some of these challenges by publicising and prioritising activity relating to our returns policy and procedures. We also intend to take a more proactive approach to engagement and consultation, be open to exploring models for both virtual and physical repatriation and co-curators.

Full lists of human remains in the collections can be found here.

A copy of our current human remains policy can be found here.