Photography and Women

As part of the Photo Oxford Festival 2020, the Pitt Rivers Museum’s staff have taken a fresh look at their huge collection of around 300,000 historic and contemporary photographs, and picked out one that for them resonates strongly with the festival's theme, ‘Women and Photography: Ways of Seeing and Being Seen’. Although working mostly from home, staff have made use of the Museum’s online database, where 65% of the collection is available in digital form online.

See the fuller picture by clicking on any image as you make your way around the exhibition.

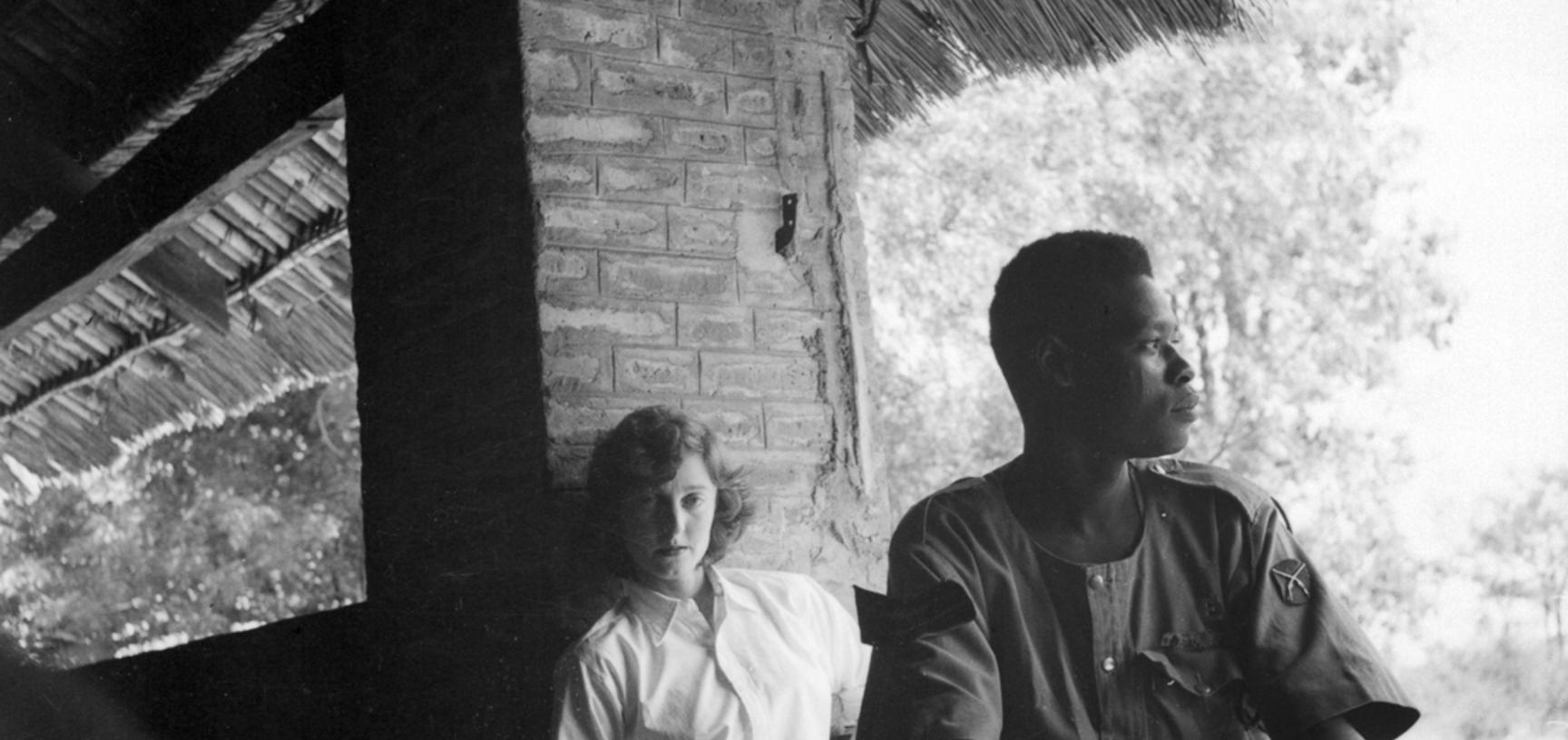

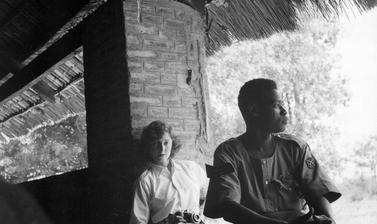

Anthropologist Jean Buxton with her camera in South Sudan (1950-1952) [1998.97.184]. Chosen by Dr Zoe Cormack, Research Affiliate.

I chose this image because it says so much about the contradictory experiences of a British female anthropologist in the 1950s. Buxton was empowered, developing her research in a male dominated environment at Oxford, but she was still subject to the ‘protection’ of the colonial state in Sudan. I’m also fascinated by how this image hints at the experience of South Sudanese interlocutors – who had a variety of roles in research projects - but are often occluded in anthropological accounts.

Group of Luo women, Kenya, circa 1902, photographed by colonial administrator Charles W. Hobley [1998.206.5.6]. Chosen by Prof Corinne Kratz, Research Affiliate.

This image of a group of Luo women shows them watching something out of the frame while they themselves are being seen and observed, engaging some of the dynamics evoked by this exhibition’s theme.

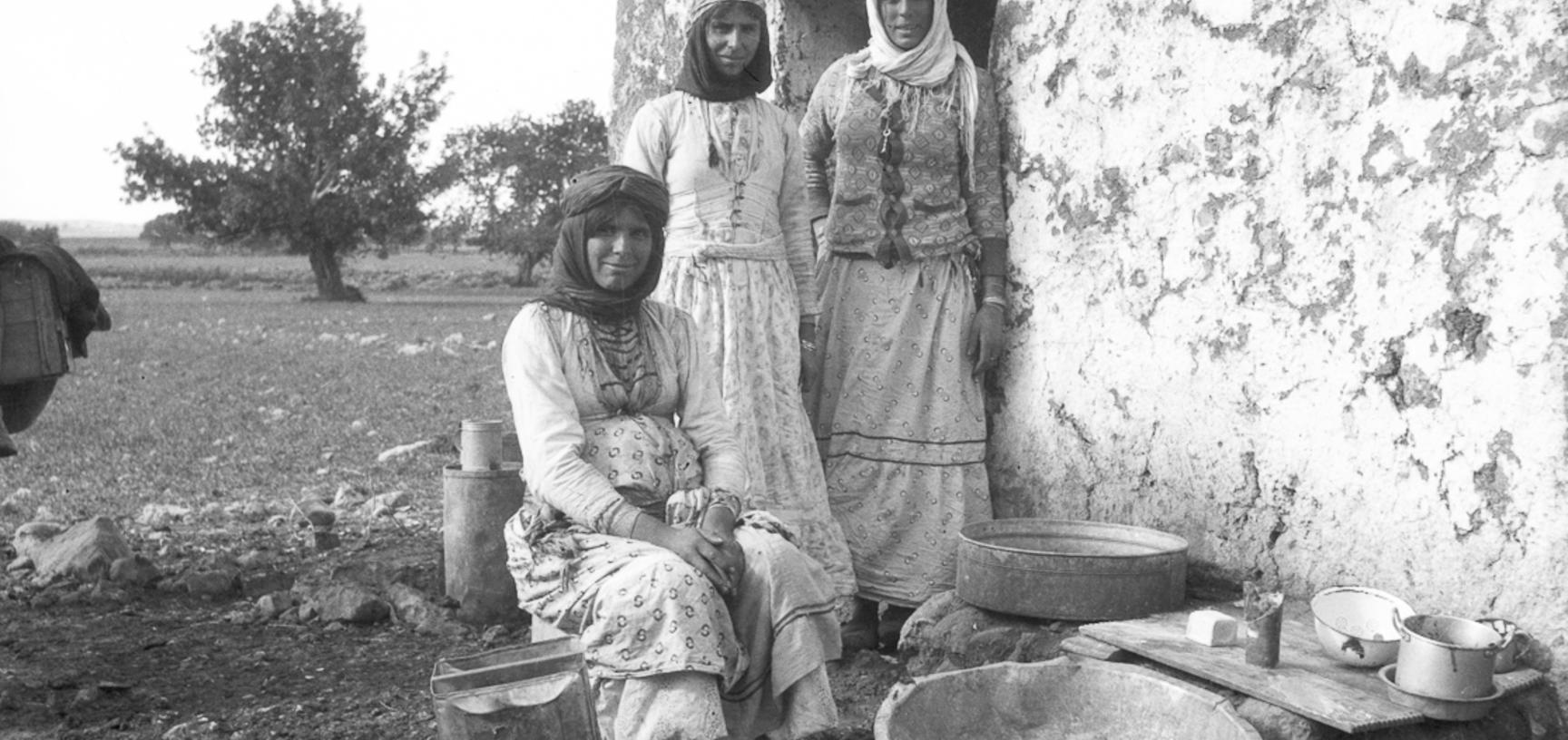

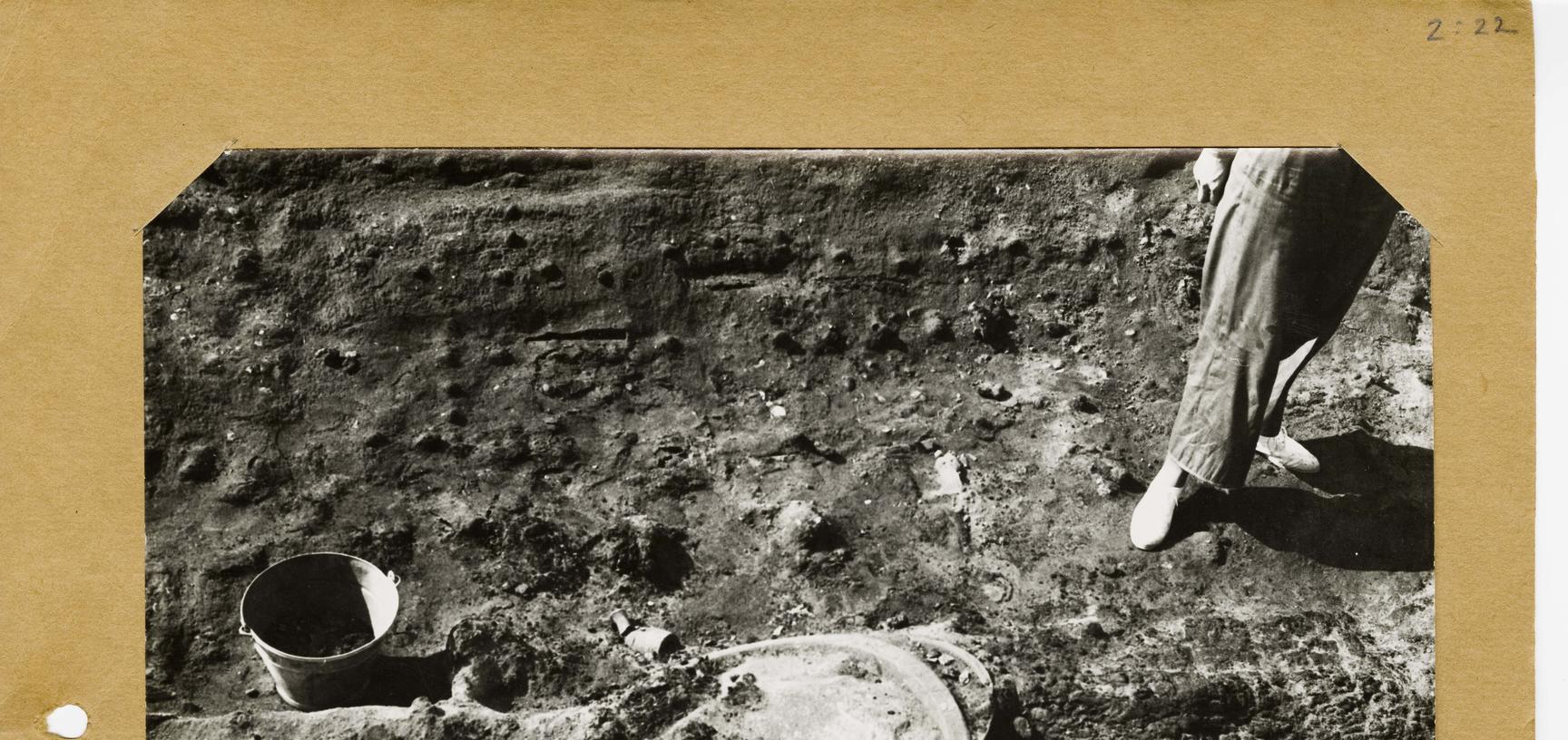

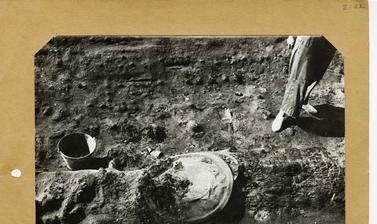

Palestinian women (named as Rashidi, Amui Haj, Yusra) working at archaeological excavation, Wady el Mughara, Israel, 1932. Photo by Dorothy Garrod [1998.294.52]. Chosen by Dr Ashley Coutu, Research Fellow.

I chose this image because it celebrates women in Archaeology. The photo was taken by archaeologist Dorothy Garrod in 1932 whilst on fieldwork in Israel. Garrod became Professor of Archaeology at the University of Cambridge in 1939, at a time when, as a woman, she was not even allowed to be a full member of the university. Depicted in the photograph is Yusra, a local woman who became an expert archaeologist through leading excavations with Garrod and Jacquetta Hawkes, the first woman to study for the degree of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge in 1929.

Kainai (Blackfoot) girls, St. Mary’s residential school, Alberta, Canada, 1925. Photo by Oxford anthropologist Beatrice Blackwood [1998.442.82]. Chosen by Prof Laura Peers, Curator Emerita for the Americas.

Residential schools were intended to strip culture from Indigenous people and assimilate them, and were harsh, often abusive environments for children. The photograph is by Beatrice Blackwood, a woman anthropologist from Oxford. Few anthropologists photographed in residential schools, and girls like these were basically held prisoner in school, away from their families, for years, unseen by outsiders. Here they are looking at Blackwood, who is seeing them. The girls’ gazes are very intent. The photograph makes me wonder what they, and Blackwood, were thinking.

Margaret Guido (1912-1994), also known as Peggy Piggott, an early twentieth century archaeologist. Photographed at the excavation of Sutton Hoo by O. G. S. Crawford, 1939. Chosen by Beth Hodgett, Doctoral Student.

Margaret Guido (1912-1994), also known as Peggy Piggott, was an early 20th-century archaeologist. This photograph was taken on 25th July 1939 by O.G.S. Crawford (1886-1957) during the excavation of the ship burial at Sutton Hoo. Guido was one of the first archaeologists on site, and the first to excavate the riches of the burial chamber. Crawford photographed her in the excavation trench standing next to one of the most spectacular finds, the Anastasius Dish. When we look at the original negative, we can see that Crawford originally framed the photograph so that Guido’s face was visible, but in later publications Crawford cropped the photograph so that the Anastasius Dish became the focus of the image. Just as Guido was cropped out of the photograph, until recently Guido’s contributions to archaeology have often been overlooked. Photographs like this are fascinating because perceptions of their value and use change over time; though the photograph has been used as a record of an archaeological find, we can use it in the present to recover the human stories of people involved in the excavation.

Beatrice Blackwood with her camera during anthropological fieldwork in Yoho Valley, British Columbia, Canada. Photographer unknown, 1925 [1998.442.105]. Chosen by Zena McGreevy, Exhibitions Officer.

I’ve selected this particular image as it actually shows Beatrice Blackwood with her camera and since she was not only intrepid as a woman going into remote parts of the world but managed in tropical and humid climates to take and process her own photos as part of her fieldwork.

Self portraits by Nyema Droma. Taken in 2018 in Lhasa, Tibet [2019.18.19.1 & 2019.18.20.1]. Chosen by Prof Clare Harris, Curator for Asia.

The Tibetan photographer, Nyema Droma, was Artist in Residence at the Pitt Rivers Museum in 2018-2019, when she co-curated an innovative exhibition of her work entitled ‘Performing Tibetan Identities’. For that show, she photographed over 30 other young Tibetans in a double-portrait format to explore the intersectional facets of identity. Her own self-portraits, created at that time, reflect the many ways that she has challenged stereotypes of female roles and agency, both in Tibetan communities and beyond.

Portrait of Irena Kipsova, Čataj, Slovakia, 1998, by the textile, embroidery and amulet expert Sheila Paine [2012.4.1447] Chosen by Alicia Bell, Collections Database Officer.

This portrait is of Irena, taken by Sheila Paine in 1988 when visiting Čataj in Slovakia. Sheila has travelled around the world learning about the traditions of embroidery in different cultures. The village of Čataj is famous for its embroidery, here Irena holds her beautiful wedding shawl. It seems as though Irena is proud to be showing her wonderful shawl to Sheila. I love the colours of the shawl in contrast to the grey wall behind her and the slight smile she wears.

A young Amazigh woman selling pottery in Sejnane, Tunisia [2018.137.488]. Photo by the textile expert Jenny Balfour-Paul. Chosen by Joanna Cole, Multaka Project Officer.

While cataloguing a recent acquisition of photographs donated by Jenny Balfour-Paul, I was drawn to this image of a young Azamigh woman selling pottery in Sejnane. This Tunisian town has long been noted for the traditional skills and techniques of its female potters. I love how the vibrant colours of the chilli peppers and corn, drying in the hot sun, contrast with the clear blue sky.

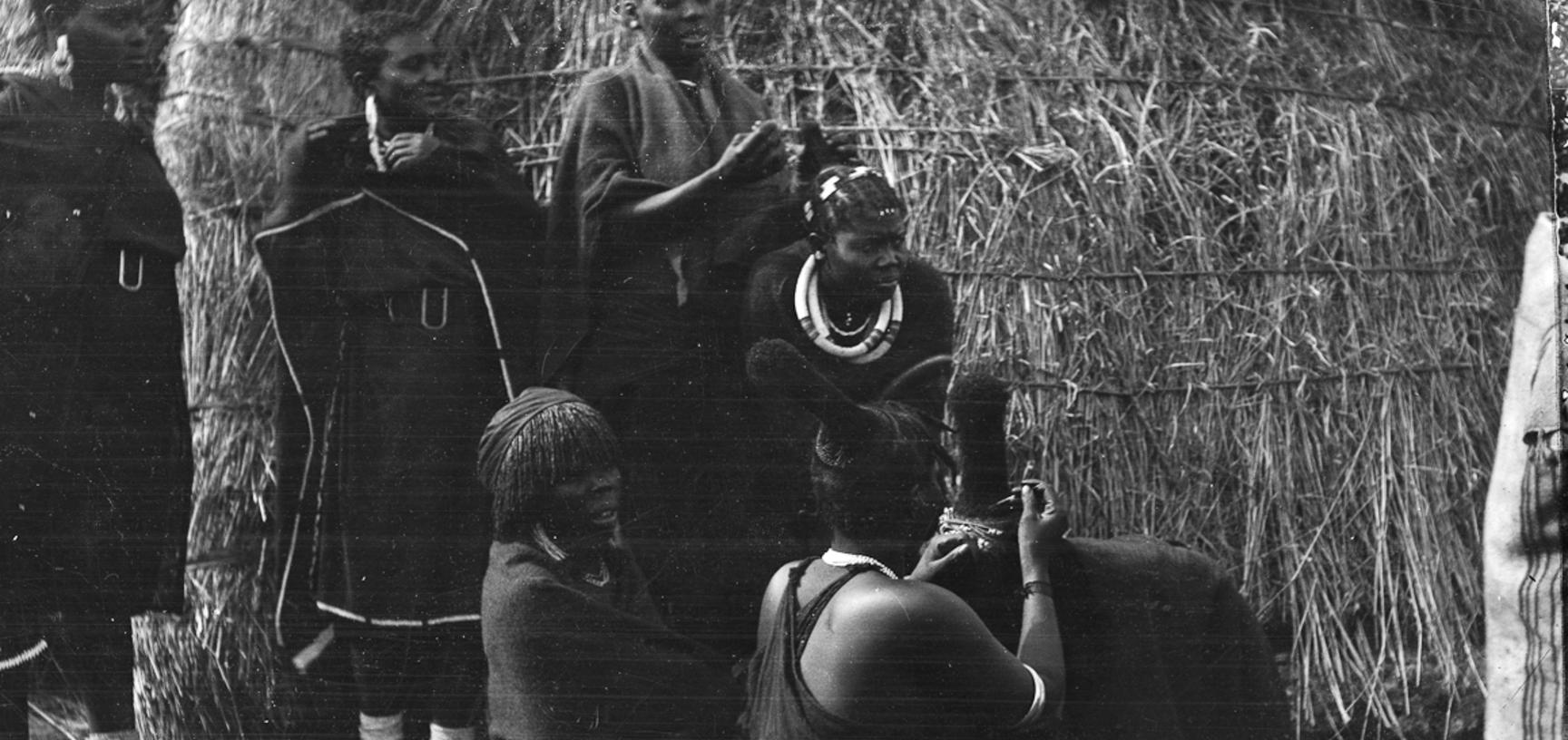

Group of Zulu women dressing each other's hair. Photo taken by Henry Balfour near Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 1905 [1999.11.27]. Chosen by Thandi Wilson, Multaka Collections Officer.

This photograph was taken in 1905 by Henry Balfour, near Pietermaritzburg in South Africa. Although his perspective cannot speak to the experiences of the Zulu women in this image, this moment frozen in time is still relatable for women around the world today. The styling of hair is universally understood as an art form and as a method of expressing identity. Afro-textured hair is incredibly versatile and can be styled in many beautiful and intricate ways. This type of hairdressing is equally practical as it is fashionable due to the delicate nature of curly hair. Braiding, twisting and threading require skill and patience often taking hours, even days, to finish. These time-consuming beautification sessions are therefore perfect opportunities for women to socialise; bonding through the act of pampering each other while catching up with friends, family and children. In fact, it's commonplace for friends to get together to practice and teach each other new techniques and ways of wearing hair.

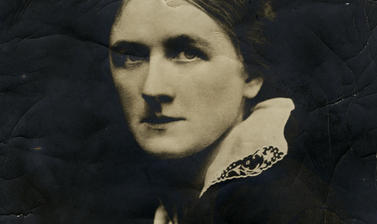

Portrait of the pioneering Polish anthropologist Marie Antoinette Czaplicka by Emil Otto Hoppé, 1915 [1998.271.41]. Chosen by Dr Jaanika Vider, Research Affiliate.

This studio photograph of Marie Czaplicka by E. O. Hoppé was taken straight after she returned from her Siberian expedition and shows how women used photography to influence and situate themselves in society at the time, Hoppé then being one of the most important society photographers.

Portrait of Minnie Wilson (later Minnie Croft), a student at the Coqualeetza Indian Residential School, Canada. Photo by Beatrice Blackwood, 1925 [1998.443.156.2]. Chosen by Marenka Thompson-Odlum, Research Associate.

She came from a clan of sturdy, strong-willed women. She came from a clan of dreamers, but she was a doer also. (Haida Gwaii Observer, 2007)

These words were written in the obituary of Minnie Croft, who 82 years earlier was photographed by Beatrice Blackwood at the Coqualeetza Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada. Unlike so many of the photographs in the Pitt Rivers Museum's collection, the subject of this photograph was named, a habit which is displayed in much of Blackwood's collecting. Thanks to Blackwood's meticulous record keeping, I was able to find out more about this young woman who stared defiantly at the camera. That direct gaze of 15-year-old Minnie speaks volumes of the woman she would become. Croft was a member of clan Skedans-Haida Nation and spent most of her life as an advocate for First Nations peoples, especially First Nations women, and promoting educational opportunities for First Nations students. I chose this photo because I think Blackwood, like Croft, was a dreamer, but also a doer; and this photo is like recognising like.

Girls at a market in Chichicastenango, Guatemala. Photo by Sheila Paine 1991 [2012.4.290]. Chosen by Faye Belsey, Deputy Head of Collections.

This photograph candidly captured by Sheila Paine shows three girls sitting on the floor at a market shaded by an umbrella. They are possibly unaware that Shelia was capturing the moment on film. Markets are usually such busy places and this image reflects a moment of stillness amongst the hustle and bustle that we cannot fully see but get a small glimpse of beyond where the girls are sitting. I love the framing and vibrancy of the photograph in the layers of brightly coloured textiles the girls' wear.

Samoan missionary and family with a group of women outside the Mission Station house at Nukufetau, Samoa. Photo by George Smith for C. F. Wood, 1873 [1998.279.64]. Chosen by Prof Elizabeth Edwards, Curator Emerita and Research Affiliate.

This photograph shows a group of women, dressed in their best dancing skirts, staring quizzically and calmly into the camera. I have always found their solid, self-possessed presence provocative of larger questions not only about women’s experience on the edge of the imperial world, but the ways in which photographs hold a presence, social being and experiences people lived through. These women appear to have a clear sense of self-reference in the world. The photograph was taken in November 1873 by George Smith, a photographer who accompanied yachtsman and collector C.F. Wood on the latest of his Pacific voyages. 1873 is astonishingly early for a photographic record of this region – a scatter of islands in the north-western Pacific. Some of these women, living their lives on Nukufetau, may well have been born before photography’s explosion onto the world, they’d only have to be 33 or 34 years old. This makes their robust photographic presence all the more mesmerising. There is something about this photograph which points at the limits of photographic knowledge, to a ‘beyond’.

They are standing by the mission church, only built in 1870, and group around the Samoan missionary, Sapolu, his wife Karolina, and mission servants. Missionary wives were hugely important and it is very likely that Karolina had a close relationship, even friendships, with these women. This photograph is also interesting because it points to the fragile complexities of colonial encounter. Nukufetau and neighbouring islands, which have cultural affinities with Samoa and with larger Polynesia, did not become a British Protectorate until 1892. Yet networks of pre-territorial colonialist relationships suffuse this photograph, and not only in the presence (behind the camera) of George Smith and Mr Wood. Sapulo was trained by Western missionaries at the Protestant London Missionary Society mission outpost in Samoa. Samoan and other Polynesian missionaries worked widely in the Pacific where they were seen as strict and efficient. For their part, the people of Nukufetau and their neighbours were, for reasons of local politics, seen as receptive to mission endeavours. This photograph stands for a moment in a complex and negotiated world.

Ursula Graham Bower in India, 1947-8. Photographer unknown [1998.309.2650]. Chosen by Julia Nicholson, Curator and Joint Head of Collections.

I have chosen this image of Ursula Graham Bower, which shows her in functional working clothes, ready to get on with any task. She had visited to the Naga Hills at the age of twenty three and relished the challenge of living in a mountainous land among Naga communities. When she was invited to go on a visit with the state engineer to inspect bridges, other members of the colonial adminstration were shocked and critical: "You'll never stand the marching" said a captain "You'll go sick in the Barak and be carried in and then you will know all about it”. She proved them wrong, worked extensively in the area which under British colonial administration was called the 'Naga Hills' and in 1942 was invited to join the 'V' force guerrilla unit to protect the area from invasion by Japanese forces. Her ability to handle a gun, which her father taught her when she was young, clearly proved to be a useful skill for a woman. She dressed accordingly…

Women with coffin of a child, covered in funerary wrappings, Lakeba, Lau Islands, Fiji, 1909-14. Photograph by Arthur Maurice Hocart [1998.300.293]. Chosen by Marina de Alarcón, Curator and Joint Head of Collections.

One of the images that I find the most powerful in the Museum’s collection is one that I feel rather uncomfortable even suggesting. The image is a photograph taken in Fiji by A. M. Hocart. Every time I look at it it feels like a smack in the face and I take a sharp intake of breath. The image is described as “View of funerary wrappings laid over the coffin of a deceased child.” Two women are sitting behind a coffin covered in a matwork shroud. The expression on the faces of the women is agonising. The image feels like a huge intrusion. I cannot begin to imagine the massive sense of entitlement the photographer must have had to take this picture. Was the shot followed by an apology, or some form of condolence? Would a woman, especially a mother, ever have taken this image?

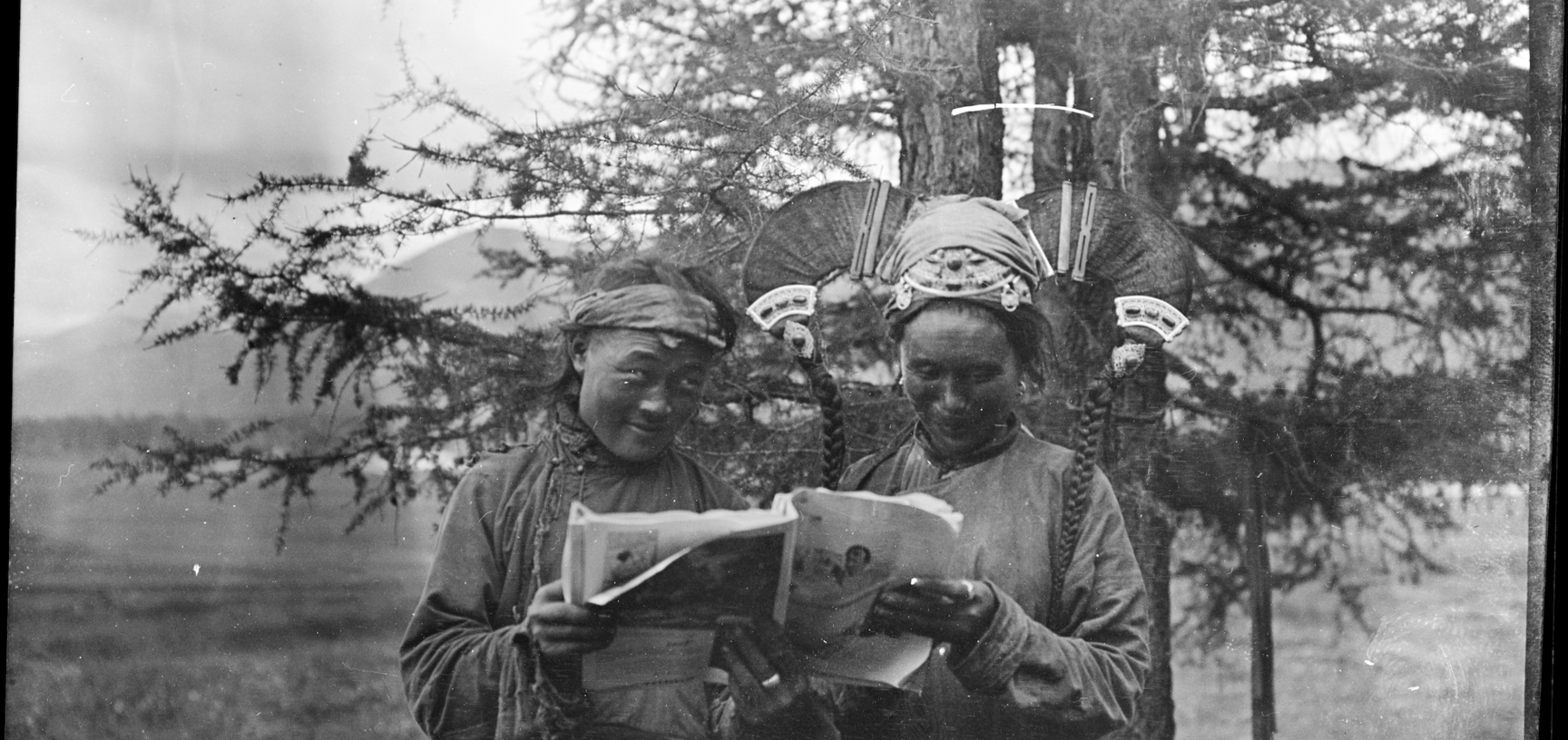

Two Mongols reading Life magazine, northeast of Urga, Mongolia. Photograph by Yvette Borup Andrews, 1919 (photograph courtesy of Library Special Collections, American Museum of Natural History (AMNH241817)). Chosen by Dr Laurel Kendall, Research Affiliate & Curator of Asian Ethnographic Collections, American Museum of Natural History.

Yvette Borup Andrews, while documenting a 1920s fossil hunt in the Gobi desert, shares her copy of Life magazine with a group of Mongol women, and takes their picture.

![Kainai (Blackfoot) girls, St. Mary’s residential school, Alberta, Canada, 1925. [1998.442.82] Group of Kainai Blackfoot girls at St. Mary’s residential school in Alberta.](https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/listing_slideshow_image_thumbnail/public/prm/images/media/1998_442_82-o.jpg?itok=GUdqTKYf)

![Portrait of Irena Kipsova, Čataj, Slovakia, 1998, by Sheila Paine [2012.4.1447] Portrait of Irena Kipsova.](https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/listing_slideshow_image_thumbnail/public/prm/images/media/2012_4_1447-p.jpg?itok=M9hxlLh-)

![A young Amazigh woman selling pottery in Sejnane, Tunisia [2018.137.488]. A young Amazigh woman selling pottery in Sejnane.](https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/listing_slideshow_image_thumbnail/public/prm/images/media/2018.137.488.jpg?itok=JB9bMQ-C)

![Group of Zulu women dressing each other's hair. Photo taken by Henry Balfour near Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 1905 [1999.11.27]. Group of Zulu women dressing each other's hair.](https://www.prm.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/styles/listing_slideshow_image_thumbnail/public/prm/images/media/1999_11_27-o.jpg?itok=Ks4oP_o4)