Matt Smith: Losing Venus

Losing Venus, consisting of multiple installations by artist Matt Smith, highlights the colonial impact on LGBTQ+ lives across the British Empire and seeks to make queer lives physically manifest within the museum. From 1860 onwards, the British Empire criminalized male-to-male relations, imposing lengthy prison sentences, and the legacy of these legal codes lives on. Of the 72 countries in the world with anti-gay laws, 38 of them were once subject to British colonial rule. As a response to these colonialist gender laws, Losing Venus seeks to place contemporary discrimination, which is still affecting the lives of many around the world, at the heart of one of the cultural centres of the country which exported it, examining their impact through the lens of sexual identity and gender fluidity.

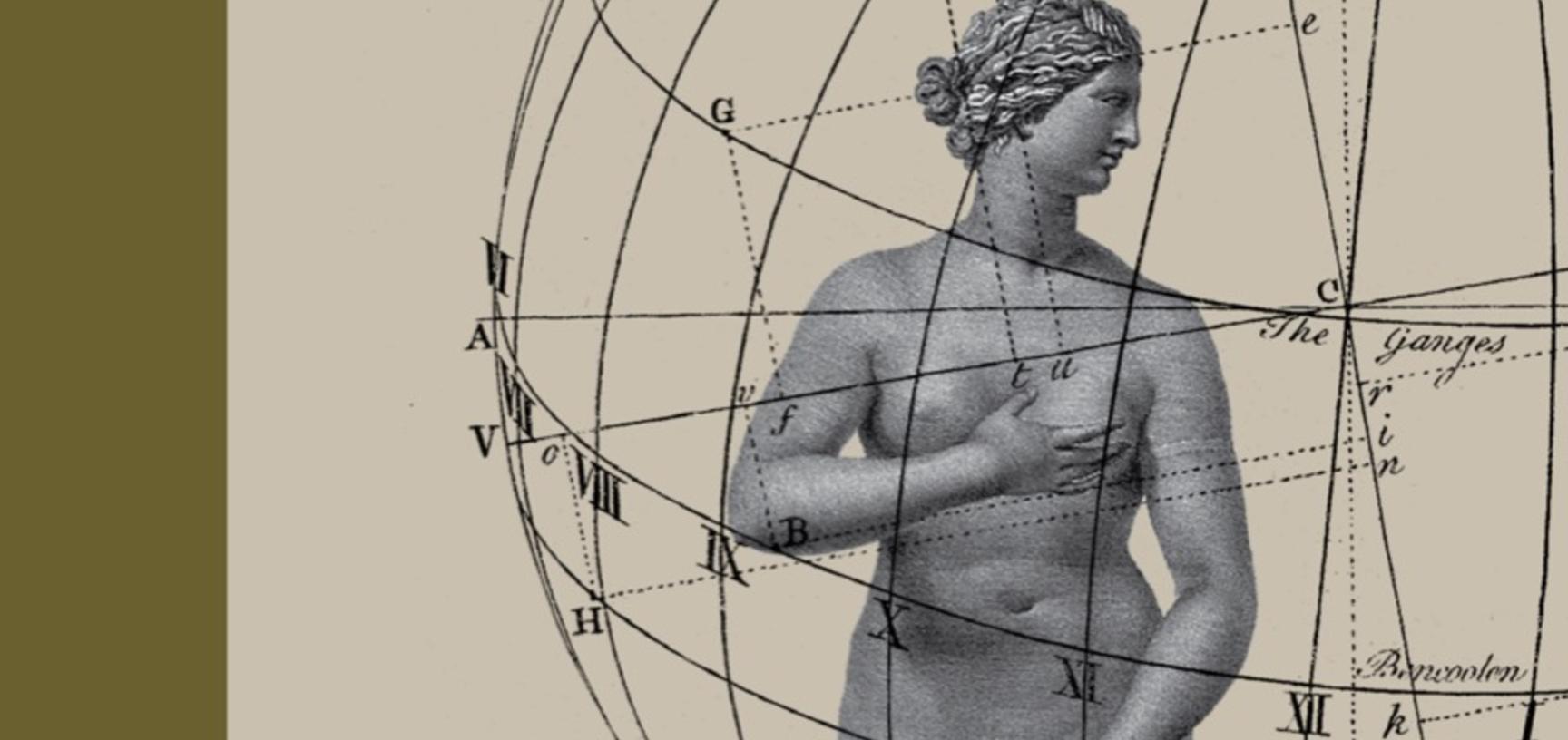

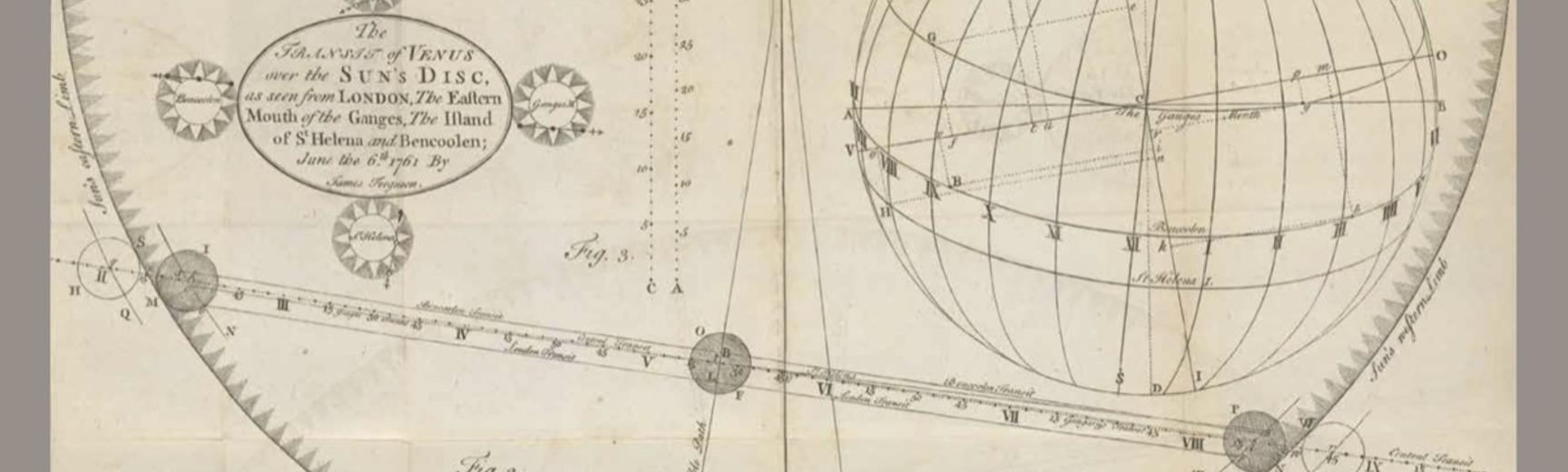

The title Losing Venus is a reference to the idea of love and gender, but also references the purpose of Captain Cook’s first voyage – to measure the transit of the planet Venus. The installation comprises four main parts located on the Lower Gallery (first floor) of the Pitt Rivers Museum.

About the Artist

Matt Smith was born in 1971 in Cambridgeshire. His artistic practice involves unpicking the work of establishment organisations and shifting their – and their visitors’ – points of reference. His ground-breaking exhibitions in the past decade include Queering the Museum at Birmingham Museum (2010), Other Stories at Leeds University Art Collection (2012), Flux: Parian Unpacked at the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, in 2018, and Spode: A 31 Note Lovesong at the V&A (2016) and Gustavsberg Konsthall, Stockholm (2019). He has also been closely involved in collaboration with the University of Leicester and in the National Trust’s ‘Prejudice and Pride’ project.

Matt Smith was Artist in Residence at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2016. He has won numerous awards including the Young Masters Maylis Grand Ceramics Prize (2014) and ‘Object of the Show’ at Collect at the Saatchi Gallery (2018). His work is held in many museum collections including the V&A, the Fitzwilliam Museum, the Walker Gallery, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, and Brighton Museum and Art Gallery. He has a PhD from the University of Brighton and is Professor of Ceramics and Glass at Konstfack University, Stockholm, and a Visiting Fellow at the University of Leicester.

Losing Venus

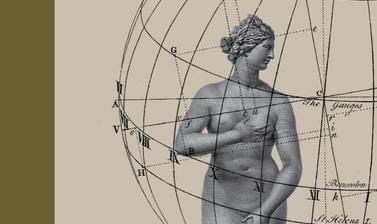

In 1768, Captain James Cook set sail for the Pacific on the Endeavour. For more than 250 years, Europeans had explored the Pacific, but much of it remained unknown to them. Cook’s voyage was supported by both the British Admiralty and the Royal Society with the initial aim of recording the transit of the planet Venus – named after the Roman goddess of love – from Tahiti. By observing the passage of Venus between two different points on the Earth’s surface, it would be possible to calculate the distance from the Earth to the Sun, and from that the size of the Solar System.

In Britain, Cook was seen as a national hero. In Australia, and to a lesser extent in New Zealand, Cook was celebrated in monuments, statues, street names and postage stamps, and elevated to the role of founding father. The anniversaries of his landings were commemorated, emphasising the belief that his arrival was the point at which the national story began. This view has been challenged, particularly amongst Aboriginal Australians, who critique the narrative of European ‘discovery’.

The Cook Service (Didcot Case)

At the same time as Cook set sail, Josiah Wedgwood was setting up his eponymous ceramics factory. The Cook Service is the celebratory service that Wedgwood never made, taking landscapes and portraits recorded on the voyages as a starting point. Wedgwood did, however, make medallions of Captain Cook in the 1770s, and these continued in production up until the 1970s, a cast from which features on many of the pieces in the dinner service in this exhibition.

On the Cook Service, juxtaposed with images recorded by the Europeans, are images of Venus, the Roman goddess of love. Cook set off to find the planet of love but seems to have been one of the few members of the expedition to remain celibate during the voyages.

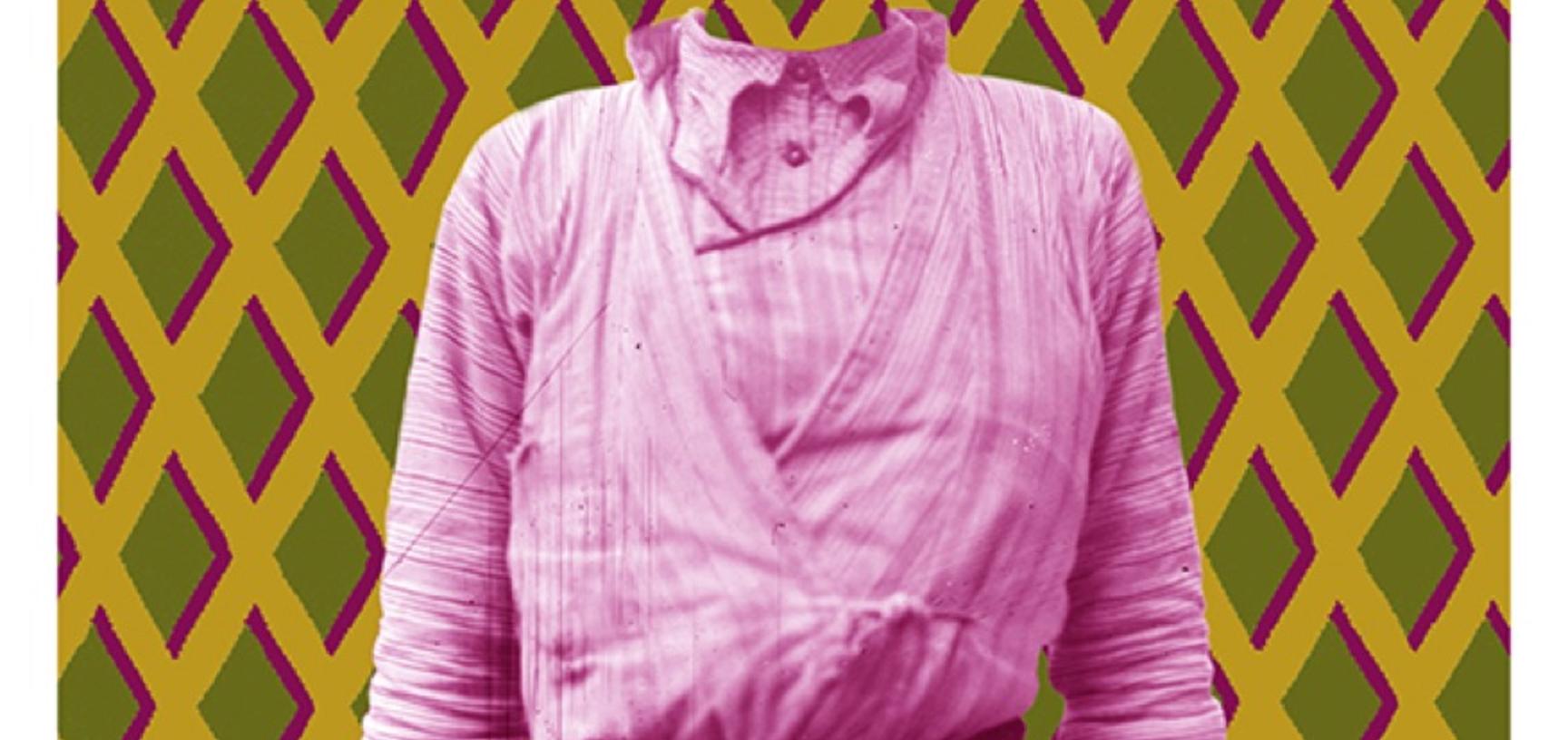

The Prints (Bow-Fronted Case)

Same-sex love featured in the records of Cook’s voyages which recorded the aikāne in Hawaii – young men attached to the court who had same-sex sexual, social and political functions.

The expansion of the British Empire which followed Cook’s explorations was to severely impact how people would be able to love. According to historians Enze Han and Joseph O’Mahoney, from the ‘1860s onwards, the British Empire spread a specific set of legal codes and common law throughout its colonies ... which specifically criminalized male-to-male sexual relations’, a legacy that lives on today. Of the 72 countries with anti-gay laws in 2018, at least 38 of them were once subject to some sort of British colonial rule.

Each of the prints is based on photographs from the collection at the Pitt Rivers Museum. Each photograph was taken in a country where Britain either imposed or maintained homophobic legislation. It has been argued that this legislation was mostly a response to colonial panic about Western behaviour overseas, but the impact on the local population was to change how many societies viewed same-sex love and gender diversity.

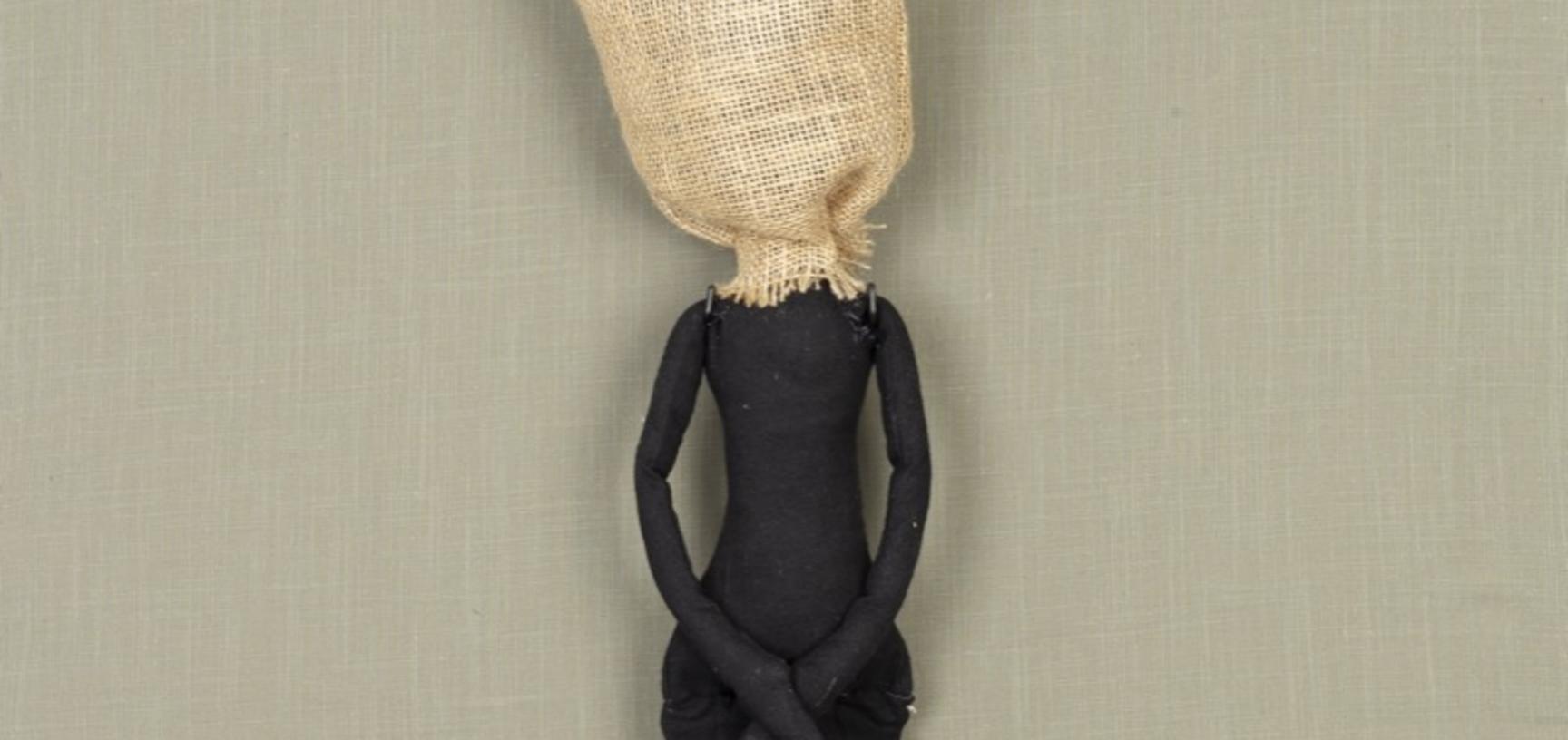

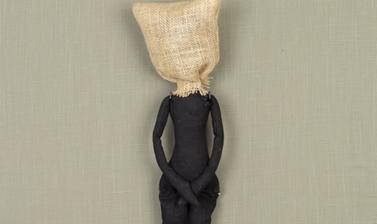

The Dolls (Puppet Case)

It is important to recognise and respond to the Pitt Rivers Museum’s legacy of Victorian morality, since it not only collects and displays, it also educates, and shapes culture. Within the displays is a case whose label reads: ‘[a] common use for dolls is to teach children about adult life, roles, and beliefs’.

Centuries of heteropatriarchy, from Victorian morals through to Clause 28, have ensured that children have only been taught about certain adult (heteronormative) lives, a view imposed through British colonisation around the world. I was interested in what dolls we might use if we were to teach children about four different experiences of LGBTQ+ adult life around the world, because in different places and at different points in history other ways of being have been accepted, and sometimes celebrated.

Historically and geographically, other ways of being have been accepted and sometimes celebrated. From the acceptance of gender diversity in Samoa through to the historic acceptance of same-sex intimacy amongst samurai, queeness has always been there, whether Europeans were willing to see it or not. Cultures respond and adapt to difference in subtle and nuanced ways. That the number 24 brings with it queer resonance in Brazil requires cultural knowledge and argues for the need to allow those immersed in a culture to interpret their own objects, bypassing a Western European lens.

In several countries, LGBTQ+ people are being imprisoned for loving members of the same sex. Brutally, in September 2011, three men were executed for sodomy in Iran; no doll can prepare a child to learn that this will be their adult life.

The Banners

Queer love is just one of the many intimacies that the museum has traditionally disregarded. There are twelve love tokens catalogued in the collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum. None of the entries describe who they were given to, or by whom. While each object is described in detail, the human relationships have been erased. When objects come into museums they are usually divorced from their former owners and fitted into the taxonomies of the institution.

This stripping away of context and meaning is particularly ubiquitous with queer histories and narratives, either because of intentional homophobic erasure or because the queer resonance of the objects was unknown to the people who collected and catalogued the objects, connections so far outside their morality and understanding as to be unidentifiable. These banners act as a reminder that while museums can tell us much with the objects they hold, there is so much about the people who used them, and their loves and desires, that remain unknown.

Acknowledgements and Credits

- Exhibition curated by Matt Smith and Andrew McLellan

- Installation by Adrian Vizor

- Slideshow by Tim Myatt

- Special thanks to Philip Grover, Jozie Kettle, Christopher Morton and William Pearce

- Supported by Arts Council England and Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design

You can read an article by artist Matt Smith on the motivation and inspiration behind his artwork and multi-part installation Losing Venus online here (Blogger/Photograph and Manuscript Collections). You can also read an interview with Matt Smith about his Losing Venus exhibition online here (OX Magazine).

A new book has been published to accompany the Pitt Rivers Museum’s exhibition: Matt Smith, Losing Venus (Stockholm: Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design, 2020). You can order the book online here (Ashmolean) or below, or buy it in person from the Pitt Rivers Museum Shop.

Losing Venus Teacher's Notes (pdf)