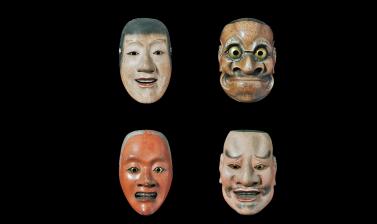

Conservation case study: Noh theatre masks

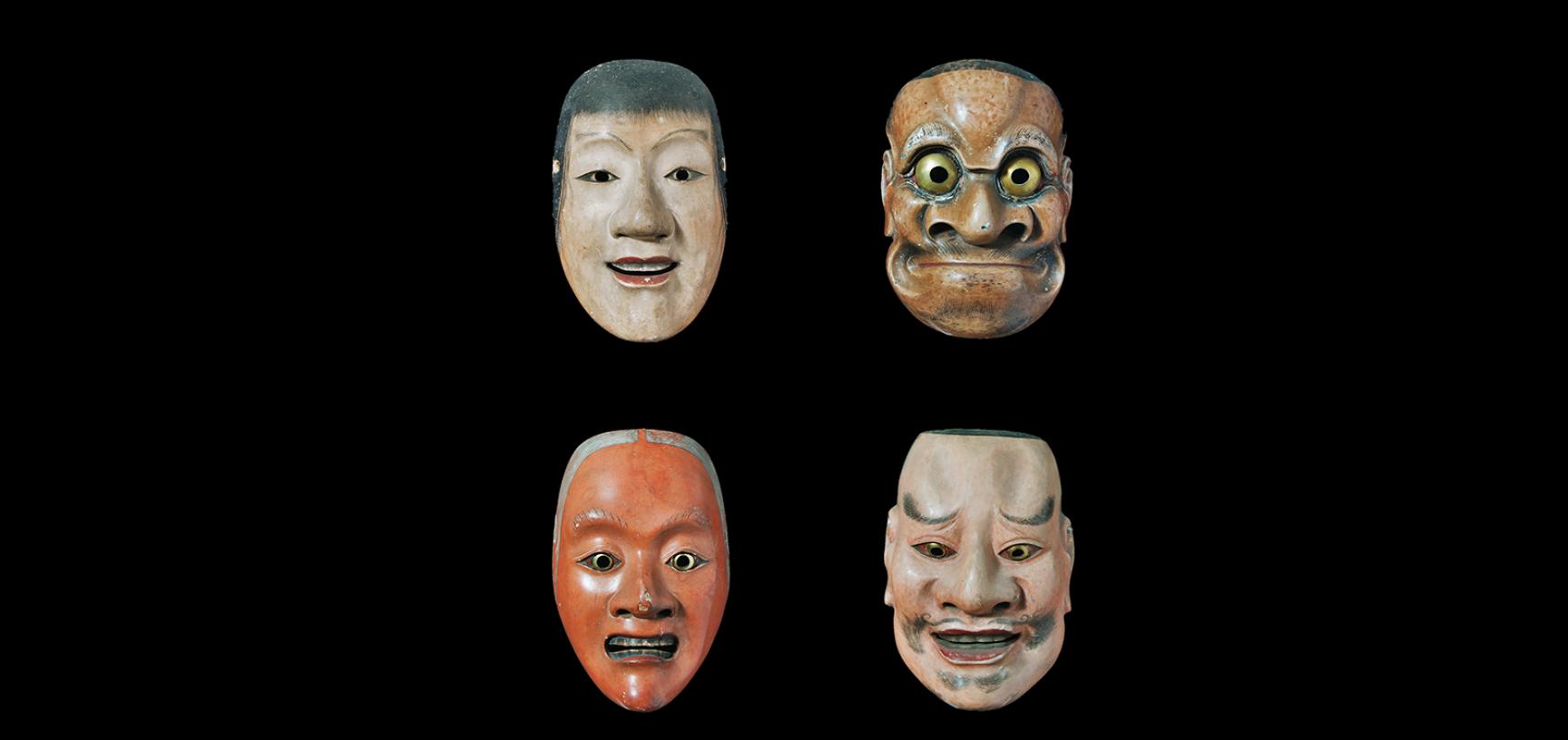

The Pitt Rivers Museum holds a collection of 52 masks, which were used by the Kongo Noh School for many years. They were purchased in Kyoto in 1879 by Basil Hall Chamberlain on behalf of General Pitt Rivers. At the time of purchase there were thought to be only two more superior collections of Noh masks in Japan.

The collection represents most major character types, with the oldest thought to date from the early 15th century and the most recent from the 1840s.

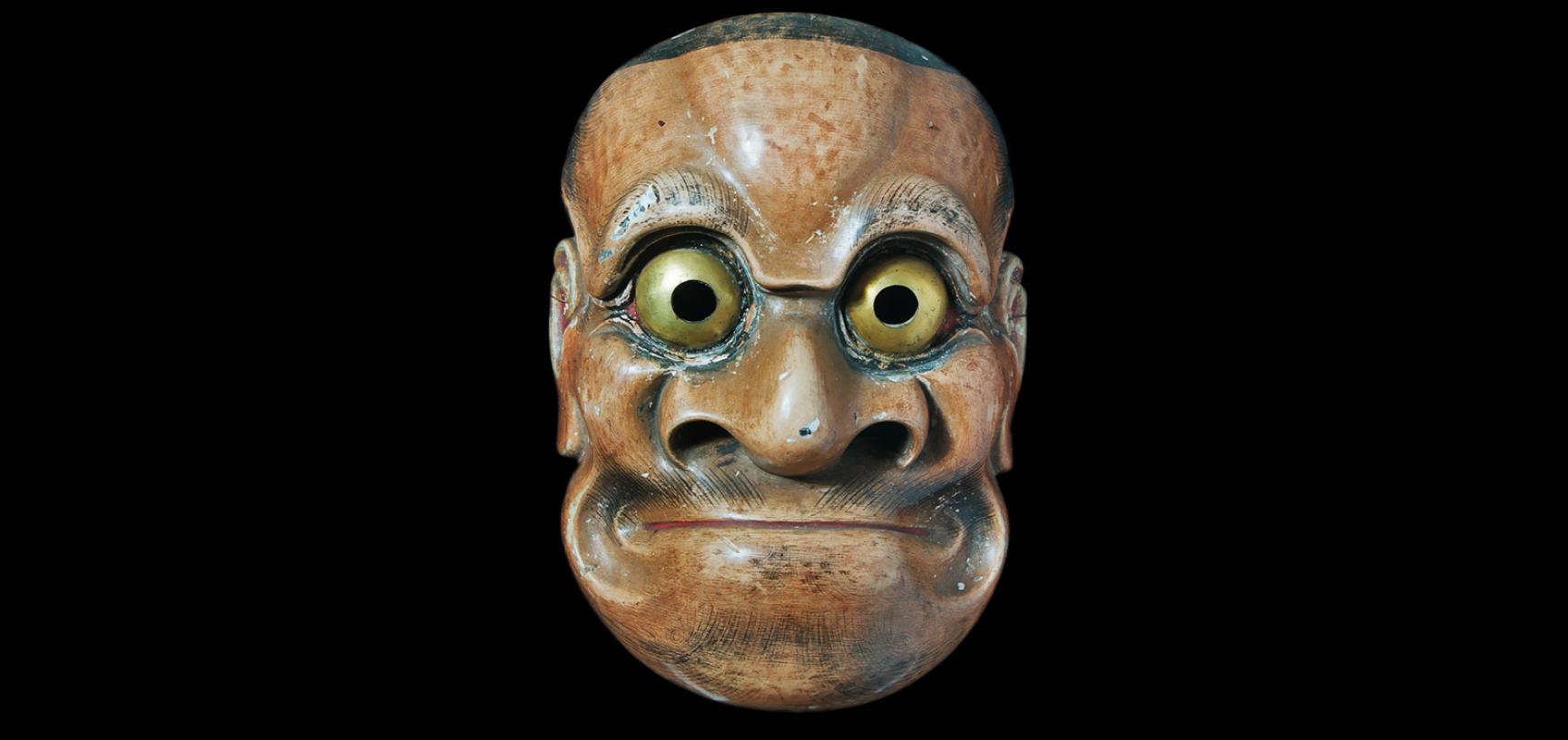

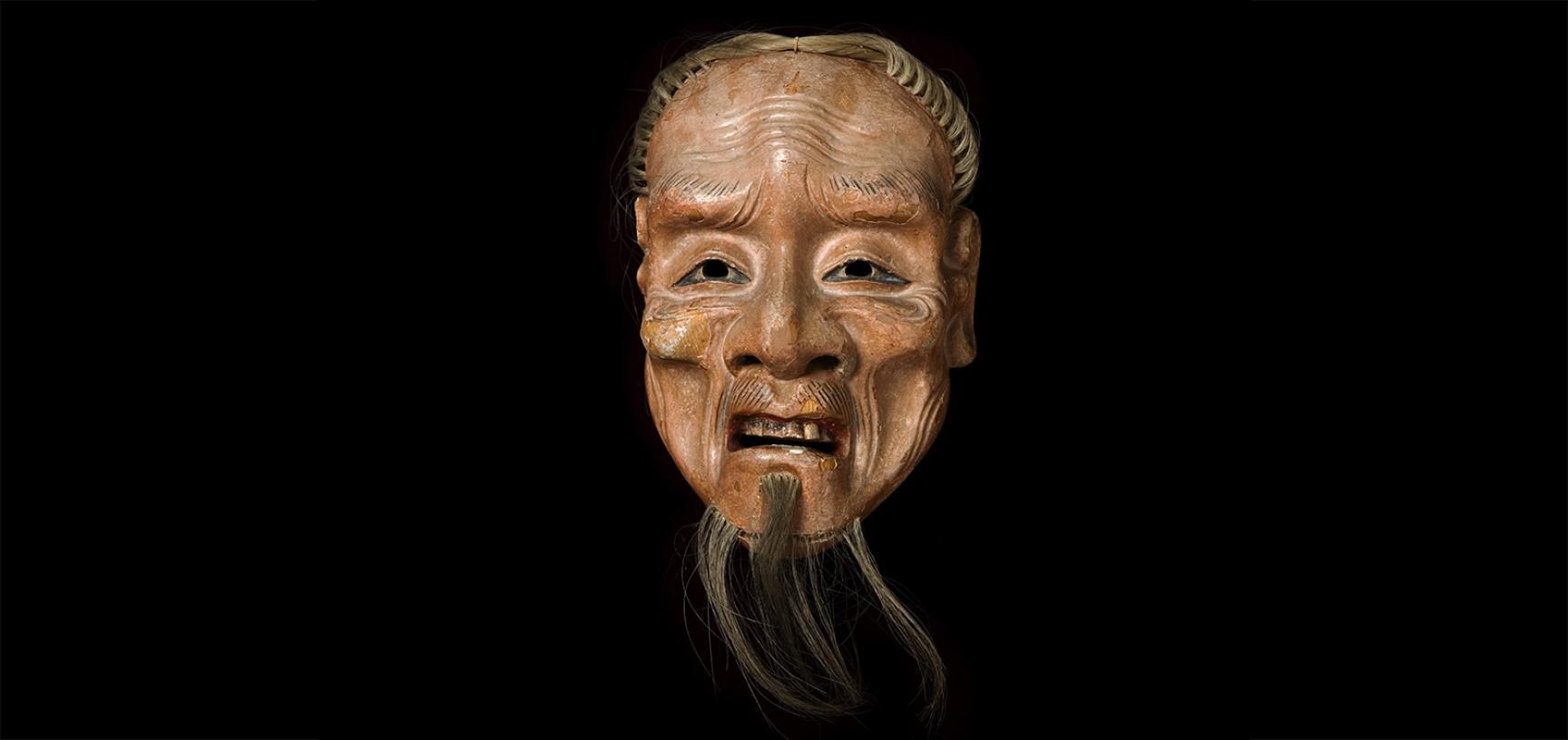

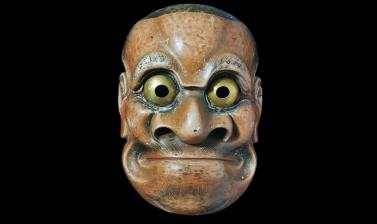

Noh masks were traditionally carved from Japanese cypress (hinoki, Chamaecyparis obtusa) and the outer surface painted with a white pigment of powdered oyster shells (gofun) mixed with animal glue (nikawa) and water. Facial details would then be painted using earth, mineral or plant dye pigments in powder form mixed with water and glue. Other materials include brass sheets and human or horse hair.

The backs of the masks were finished in a number of ways, and makers would often add a carved or painted inscription. Given that the masks were used for performances over many years, they were also repaired and surfaces retouched. When in use it was common for successive actors to adapt the interiors of the maks to make a more comfortable fit by either sanding down or packing out certain areas. 38 of the masks were selected for redisplay based on type and condition.

The masks were photographed and prioritised by the extent of conservation required, with those requiring minor treatment being dealt with first in order that they could be safely passed to the dispaly team for new supportive mounts to be prepared.

Many of the masks had suffered from shrinkage of the wood resulting in cracking and loss to the gofun top layer. The most common areas of damage were the sides containing holes for the ties that would have secured the mask to the face; the top of the head and chin where it would have been held; and the tip of the nose, where it had been laid face down on a hard surface.

These areas were stabilised with the application of a conservation grade, water-based adhesive or consolidant. Depending on the extent of the damange, the consolidant was applied either with a brush or under the surface using a syringe. When using the syringe method, the damaged area was first wetted with a solvent to aid penetration. As the consolidant was water-based it was able to rehydrate the wood, slightly soften the gofun and pull the surface layer back down to adhere to the wood.

During the project, it was often nescessary to determine if surface treatments were the result of Museum intervention or applied during use. In some instances it was necessary to stabilise aesthetically disfiguring repairs made during use given that this was an intrinsic part of the object's history. Care was also taken to secure the masters' inscriptons, as these are vital for future research. As conservators work very closely with objects they are well placed to see and interpret details. During this conservation project, Museum conservators updated the Museum's database with additional information, such as materials, dimensions, technologies, makers' marks and repairs made while in use.

A total of 102 hours of conservation work was completed on the mask collection by one conservator. Some masks took as little as 45 minutes while the longest took 22 hours.