Bad Boys & Broken Hearts

Bad Boys & Broken Hearts

An installation at the Pitt Rivers Museum by Zina Saro-Wiwa

Special Exhibition Gallery, 28 Jan 2023 – 7 Jan 2024

Zina Saro-Wiwa is a British-Nigerian environmental artist whose practice explores the spiritual ecologies of the oil-cursed Niger Delta of her birth. Saro-Wiwa’s family’s ancestral home is Ogoniland, a rural kingdom outside Port Harcourt, which was at the centre of terrifying and destructive struggles with Shell Oil and the Nigerian military government during the 1980s and early 1990s. Saro-Wiwa challenges how Ogoni masks and masquerade are presented and how they are seen by the viewing public in ethnographic museums all over the world, including the Pitt Rivers Museum. She prompts us to think beyond their places of origin to consider how masks can be deployed for deeper cross-cultural connection and introspection.

Bad Boys & Broken Hearts is a new installation by Saro-Wiwa that addresses museology, anthropology and spiritual ecologies. It is a work about masquerade that features no masks at all. It unmasks not merely the costumed dancer, but the emotional universes and economic realities of the men behind the masks. Saro-Wiwa subverts the use of vitrines - the glass cases which display museum collections - to explore the dreams of two Port Harcourt-based Agaba masqueraders in their bedrooms. In the museum viewers gaze onto apparently inanimate masks, but in Bad Boys & Broken Hearts intimate portraits of masqueraders and their worlds gaze back.

Though the men are middle-aged, the moniker ‘bad boys’ is local parlance alluding to how local people view the youth gangs, cults and masquerade groups of the Niger Delta. Both men, whose bedrooms are reconstructed in this installation, are happily married and live with their families in the Ibadan Waterside of Port Harcourt. Their stories capture universal emotions of love, joy and hope combined with tales of loss, fear and heartbreak. But there is a more profound heartbreak that extends beyond the personal and in this installation Saro-Wiwa asks 'does a permanent sense of socio-political heartbreak lie at the heart of the Niger Delta experience? And how does this societal grief manifest itself in the bodies and cultural performances of its citizens? Moving beyond narratives of masks as artefacts of rural history, this exhibit announces that masking is an art form of the urban present, speaking to modern day hopes and hurt.

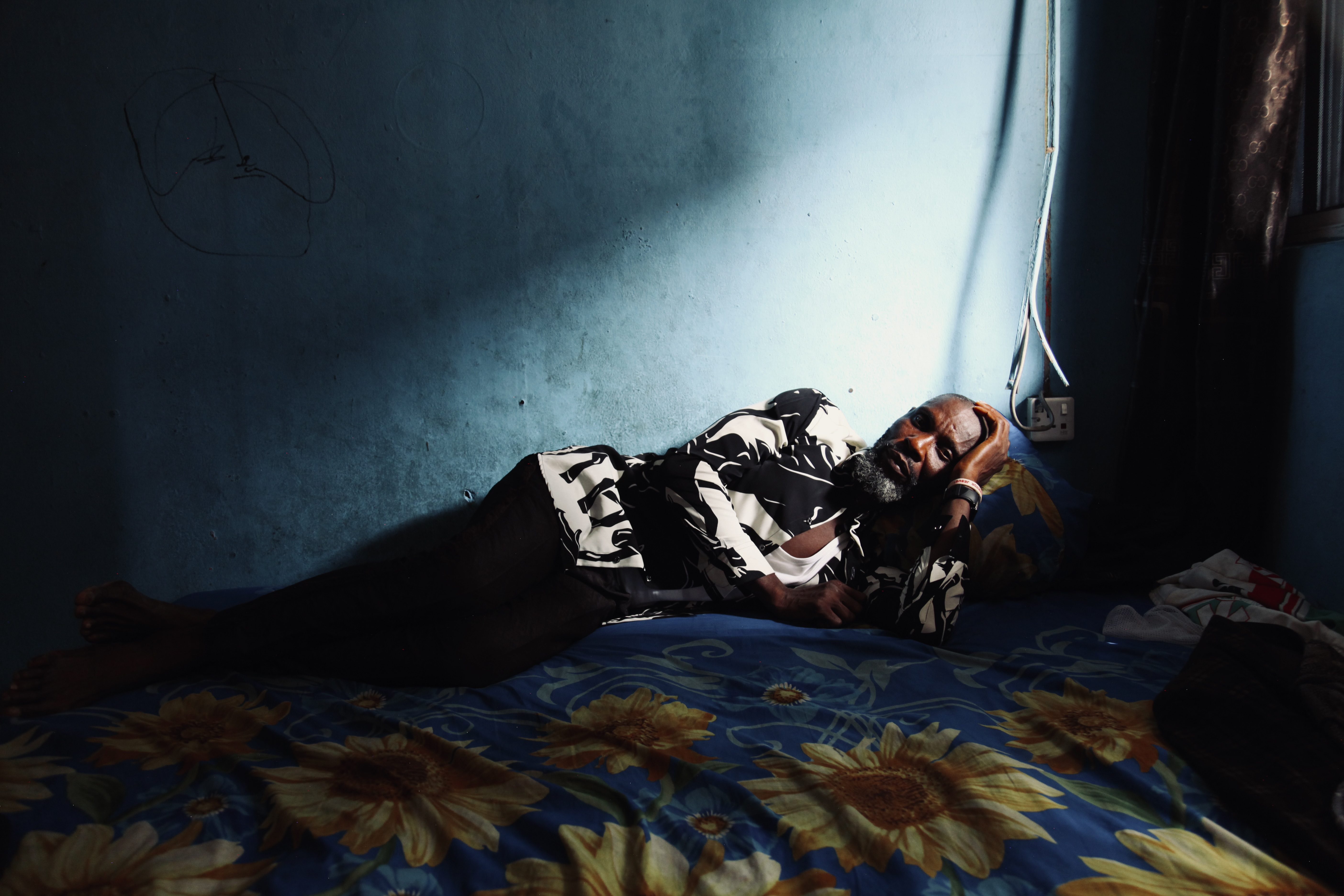

Portraits on this page include Neenukuu Kpogah (green room) and Nicholas Kuapie (blue room).

Images © Zina Saro-Wiwa

One Love: Keep Us Together

This gallery conjures up the bedrooms of two masqueraders in an encounter with their inner worlds. As a place where the spirit dreams and shapeshifts, the bedroom is a prism refracting and projecting their lives. The bedrooms belong to veteran urban masqueraders Neenukuu Kpogah (green room) and Nicholas Kuapie (blue room). Both live in the slum community of Ibadan Waterside in Port Harcourt. Neenukuu is a drummer, dancer and youth leader, and works as a security guard. Nicholas, a tall, slim and well-dressed 44-year-old, works as a driver for a wealthy Port Harcourt entrepreneur. Both are members of a Port Harcourt troupe named Gwara Cultural Dance Group. Their motto is the cry ‘One Love!’ to which the group responds ‘Keep Us Together’. Each room is a near replica of their bedroom. The sheets, shirts, shoes and artefacts that appear in the videos were gifted to the artist to furnish the installation. But these are not just bedrooms, they are ‘heartscapes’, a reflection on power, poverty, strength and vulnerability.

The larger videos show the men in repose against the sounds of their breath and their heartbeats. The smaller videos depict the interaction between landscape, dreams and desires as the men move through their slum to the waterfront. The videos feature the men’s favourite films: Nicholas is a devotee of the Arnold Schwarzenegger film Commando, and Neenukuu adores the films of Bollywood veteran actor Darmendra. These portrayals of strong men motivated by duty appeal to these family-oriented men who occupy the violent underbelly of Port Harcourt. The flag waving that appears is an important and powerful gesture drawn from Agaba processions. The black flag is particularly significant. According to Nicholas and Neenukuu, when the artist’s father, Ken Saro-Wiwa, was executed they began to fly a black flag to signal their grief for their fallen hero. It represents a choreography of grief and perhaps catharsis.

The bedrooms open out directly onto the noisy narrow streets of the Ibadan Waterside. It is a community filled with the sounds of one-room churches, family homes, repair shops and convenience stores. The thrum of daily life is infiltrated by the constant buzz of petrol-fuelled generators providing the power that the city’s grid does not. The films in the vitrine also feature the sound of Agaba masquerade from Neenukuu and Nicholas’ own group. This is the cacophony of dreams colliding with hardship; the sound of survival, performing as a heartbeat. The drums of Agaba, like the sound of the generator, keep the lights on. For despite the hardships there is a tender sense of love and closeness at the waterside. And we begin to understand the reasoning behind the cry ‘One Love!’. And its plaintive response: ‘Keep Us Together’.